No Gender, Only Lesbian

Or, Memes on the Brain

This is the Sunday Edition of Paging Dr. Lesbian. If you like this type of thing, subscribe!

What’s in a meme? Would a joke, told in another way, still be as true? There is a meme that has been circling around for the last couple of years that I have always loved, partially because of how smoothly it rolls off the tongue: no gender, only lesbian. Now, I’m not sure which version of this meme is the original. There is the dog version (pictured above), which is based on a prior meme about a dog and a stick, and the “galaxy brain” version (pictured below), which contains the same phrase. The first version of the dog meme I can find dates back to 2019, while the original galaxy brain meme dates back to 2017, though I’m not sure when exactly the lesbian version of this meme first arose. But I digress.

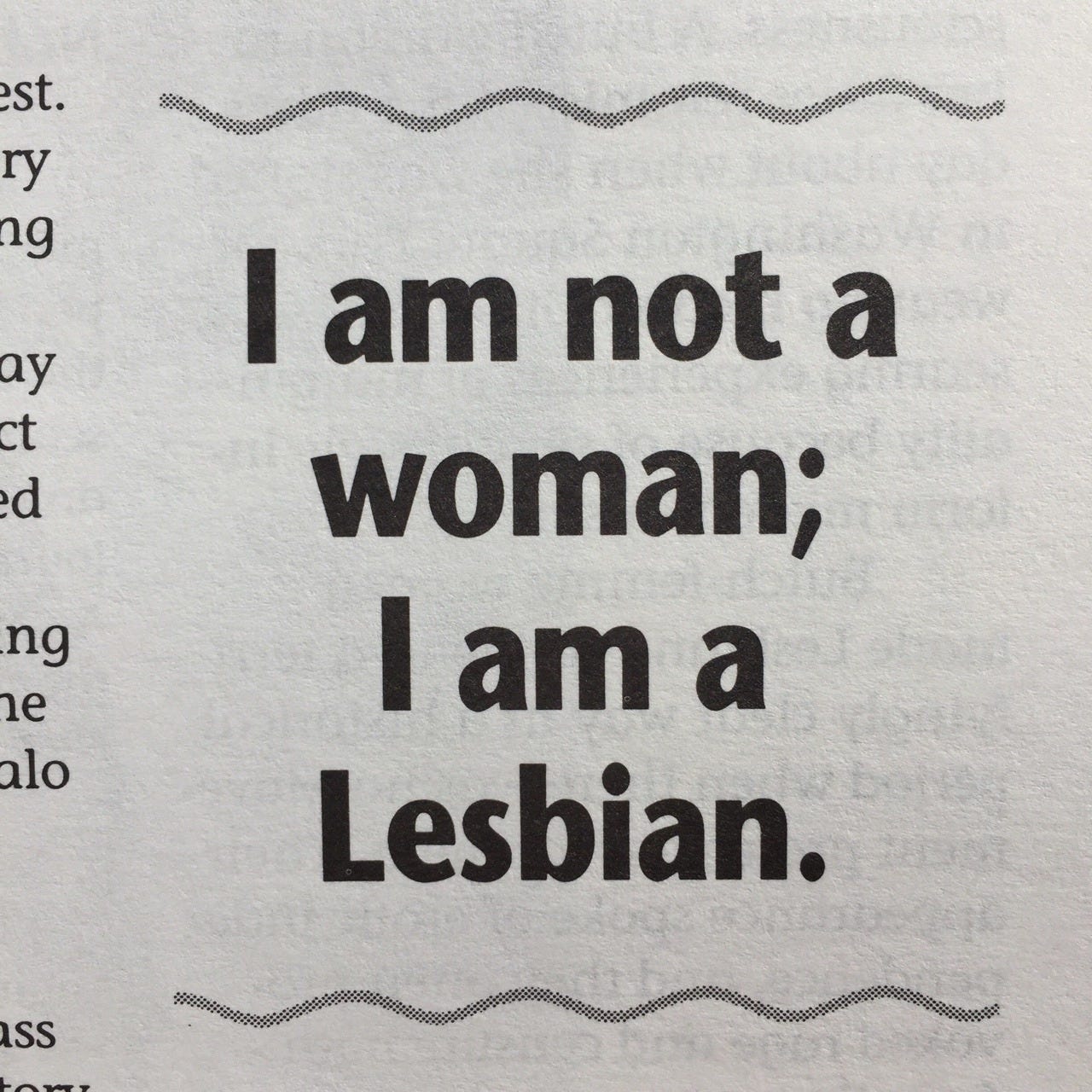

Regardless of which version of the meme came first, they both express the same sentiment, one which seems to have resonated with a number of lesbians online. Ostensibly, “no gender, only lesbian” means exactly what it sounds like. It describes someone who identifies as a lesbian but doesn’t strongly identify with a specific gender outside of their lesbian identity. Ergo, it describes lesbians who don’t necessarily identify as women, or lesbians whose gender identity can be best described as just that: lesbian.

This idea – of gender non-conformity within the lesbian community – is not new. In fact, I’ve written about it quite a bit in the last few editions of this newsletter. Non-binary people, and specifically non-binary lesbians, have existed for a very long time. Gender non-conformity itself is baked into lesbian culture, and being a lesbian already means disrupting the gender binary in some way. Indeed, in a patriarchal, heteronormative society, being attracted to men is understood as a central facet of womanhood, as is femininity. Therefore, as Jules Ryan puts it on Medium, “if you’re a woman attracted to women, your sense of gender is already unique.”

There are many examples of gender non-conforming lesbians throughout history. Leslie Feinberg, for example, the author of the indispensable Stone Butch Blues1, often identified as both a butch lesbian and a transgender lesbian. On the topic of pronouns, Feinberg maintained that they were dependent on context, indicating not the absence of gender, but rather its contingent nature.

“referring to me as "she/her" is appropriate, particularly in a non-trans setting in which referring to me as "he" would appear to resolve the social contradiction between my birth sex and gender expression and render my transgender expression invisible. I like the gender neutral pronoun "ze/hir" because it makes it impossible to hold on to gender/sex/sexuality assumptions about a person you're about to meet or you've just met. And in an all trans setting, referring to me as "he/him" honors my gender expression in the same way that referring to my sister drag queens as "she/her" does.”

Though lesbianism is often defined in binary terms, this clearly does not always reflect the lived experiences of lesbians themselves. As Alro Carracher argues in their piece I'm Proud to be a Non-Binary Lesbian,

“defining lesbianism as an exclusively binary identity is a disservice to the lesbians who have come before us, namely the gender nonconforming, often butch, lesbians whose experiences are tied to womanhood often explicitly through their love of women, but whose lesbianism - at the very same time - often estranges them from the ideals of womanhood itself.”

Though non-binary people have always existed, the terms we use to describe them are fairly modern. The term “genderqueer” was used in print for the first time in 1994, and the first person in the United States to be legally classified as non-binary only received this designation in 2016. Certainly, lesbians have also always existed under this non-binary umbrella, though the language we use to discuss these topics often seems to fall short. This, I think, is why memes like these are so powerful, and popular – they distill complex ideas into just a few words. All of a sudden, complicated definitions and difficult conversations become superfluous.

The emergence of this meme also coincides with a recent socio-cultural interest in lesbian identity, and what it means (or should mean) today. This video and its accompanying article, produced by Pink News – Can you be both non-binary and lesbian? – became a particular flashpoint for these types of conversations. The video received a number of vitriolic responses after it was posted on Twitter, with someone even commenting “we might as well leave the Amazon burning if this is the world we’re trying to save.” Certainly, the framing of the video and article contributed to this problem. The title of the article – written as it is in the form of a question – presents the issue as a matter of debate rather than a topic being discussed in good faith.

Nonetheless, the comments made by the actual lesbians in the video are quite illuminating once you get past all the chatter. Perhaps predicting the furor that would follow, one participant, Ash, said this: “At the end of the day, [the words non-binary lesbian] are terms. They are linguistic tools to describe an experience that already exists. So someone telling me I can’t be a non-binary lesbian doesn’t mean anything, because I already am one.” Indeed, one of the strange things about how identity is discussed within digital culture is the notion that other people have the power to validate or invalidate one’s identity. The phrase “that’s valid” – indicating that something someone has done or said is legitimate or understandable in the eyes of the respondent – has become common parlance on social media, with the inverse statement (“that’s not valid”) hovering just on the horizon. But, if as Ash suggests, the language of identity is used to describe one’s own experience, this external validation doesn’t need to be a part of the picture to begin with.

In Shannon Keating’s piece for Buzzfeed, Can Lesbian Identity Survive The Gender Revolution?, she describes the complicated period lesbian culture is currently in, with many of the foundational lesbian spaces of the 20th century having gone the way of the dinosaurs. As Keating puts it, “it was in those long-gone queer-specific venues — festivals, activist organizations, stores, artist collectives, bars — where queer subcultures formed and thrived. Without them, lesbianism in the 21st century lacks a coherent cultural definition.” Indeed, part of this crisis seems to be related to the definition of lesbian itself; with the ascendancy of words like queer and non-binary, some feel that the lesbian identity is slowly losing its cultural relevancy.

Perhaps, this is where the meme comes in. As a response to the idea that the very concept of lesbianism is no longer relevant, some lesbians have begun to push back at the perceived rigidity of the term itself. Similar to how the concept of bisexuality is not inherently transphobic, the argument goes, the concept of lesbianism is not inherently exclusive or discriminatory. Indeed, the “no gender, only lesbian” meme illustrates that the term still resonates with many young people in particular, and that its definition is not so rigid after all. That lesbianism can be considered both a sexuality and a gender identity indicates that its applications are actually quite expansive.

The phrase “no gender, only lesbian” has continued to find traction on platforms like Twitter and Tumblr, with some users putting the expression in their bios. This Twitter account, lesbiangender pride, is billed as a safe, positive space for non-binary or gender non-conforming lesbians, known in this context as “lesbiangender.” Another Twitter account, “radically inclusive lesbian positivity,” defines lesbiangender as “a term for nonbinary people who feel lesbianism is integral to their gender. Being a lesbian IS their gender. This can be in addition to other genders or not.”

When I posted a version of the meme on Reddit, several users agreed that it represented how they feel about their gender identity. One user commented “at this point it's easiest to describe my gender as "lesbian,” and another simply replied “yee.” Another user, who identified themselves as agender2, noted that their lesbian identity was much more important to them than their gender identity because otherwise, their “perception of [theirself] is completely devoid of gender.”

One user, a non-binary lesbian named Dee, told me that it took them a long time to understand both their gender identity and their sexual orientation because they knew they always like girls and would rather have been born a girl but have “never really been feminine.” Dee noted that seeing lesbian media for the first time – specifically the trailer for the Swedish film Fucking Amal – was the first time they were able to identify with characters or a relationship on-screen. For Dee, there is no dissonance between being non-binary and a lesbian. As they put it, “I consider myself and the women and enbies [shorthand for non-binary people] that are into me lesbian because even though I might not be very feminine, I reject masculinity. I am not male so people who are not male and into me are clearly not straight.”

While non-binary lesbians like Dee are sometimes greeted with confusion or incredulity, Dee says they don’t receive much pushback on places like these lesbian subreddits, which are often closely moderated for transphobic or hateful speech. Indeed, in many circles, this understanding of identity is commonly understood and accepted.

Certainly, this meme does not apply to all lesbians, and that’s okay. One of the great joys of the memetic form is seeing something and saying to yourself or your friends, “that’s me.” But not all of the content we consume is immediately relatable to us, even if we wish it was. What the “no gender, only lesbian” meme illustrates, really, is just how advanced our understanding of queerness has become. With only four words, a (re)new(ed) understanding of identity emerges. If the history of lesbian gender non-conformity is to be preserved, why not it be in the form of a meme?

At their best, memes can become a common language, helping users find common ground among differences. Or, they might serve as a calling card, a lighthouse to find others who relate. Either way, this meme has certainly served a purpose, if only to spotlight someone’s experience for a brief moment in time.

Because of a protracted legal battle in which Feinberg fought to reclaim the rights to the book, it is difficult to find Stone Butch Blues in print. However, prior to Feinberg’s death in 2014, ze made it available on hir website in PDF form for all to access. A new, low-cost anniversary version is also available for purchase at Lulu Books.

“Agender” describes someone who doesn’t see themselves as having any gender at all.