In New Book ‘Sick and Dirty,’ Michael Koresky Tracks Queer Presence and Absence in Old Hollywood

Did Hollywood have a gay Golden Age?

This is the Sunday Edition of Paging Dr. Lesbian. If you like it, subscribe, and share it with your friends. Upgrade your subscription for more, including weekly dispatches from the lesbian internet, monthly playlists, and a free sticker. I’m a full-time freelance journalist – your support goes a long way! If you don’t want to start a subscription, you can always buy me a coffee.

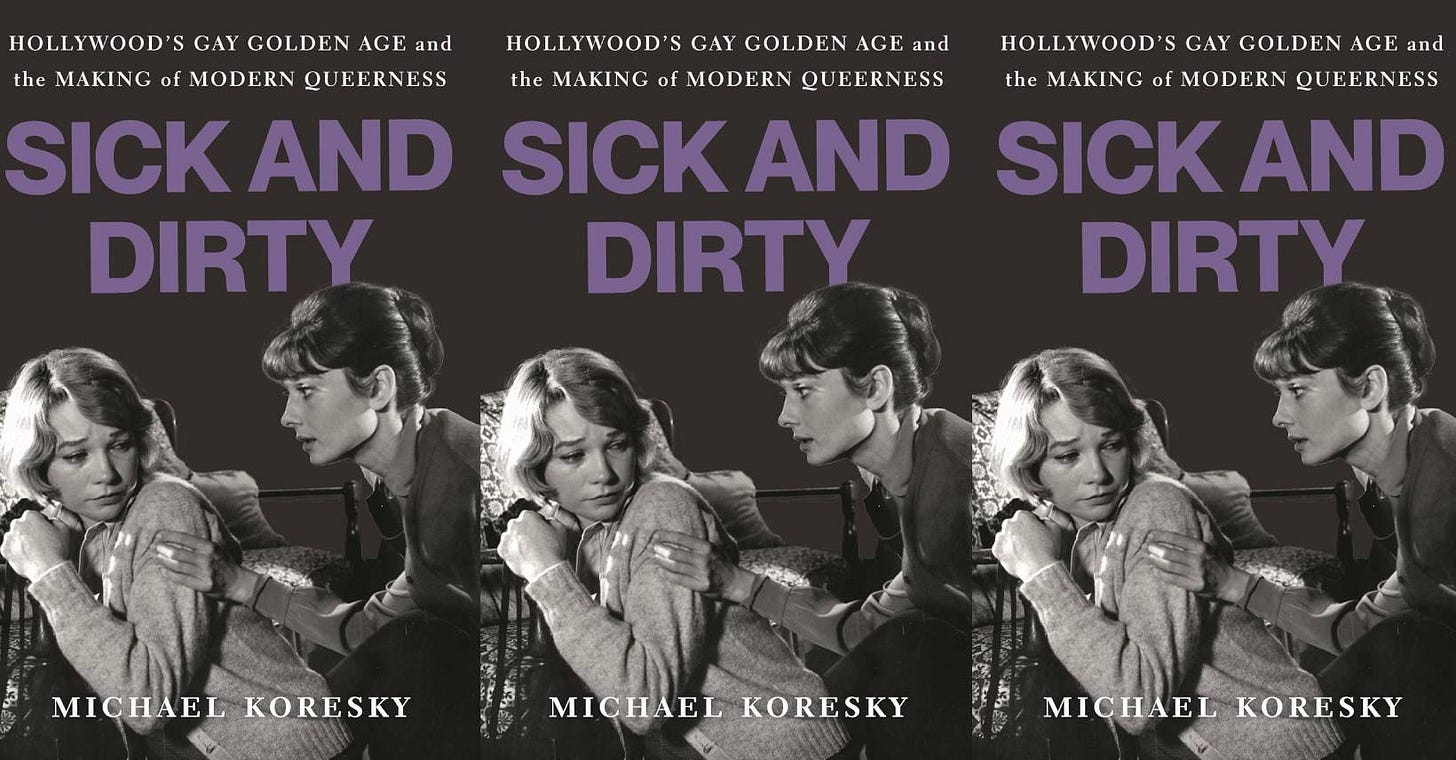

The story of Michael Koresky’s excellent book, Sick and Dirty: Hollywood’s Gay Golden Age and the Making of Modern Queerness, begins in a classroom. While teaching a Queerness in American Cinema class at NYU in 2021, Koresky showed his students The Children’s Hour, the controversial 1961 film in which Audrey Hepburn and Shirley MacLaine play women at the center of a rumored lesbian affair. Often derided for its supposedly retrograde depiction of queerness and reliance on gay tragedy, Koresky was surprised by how many of his students were touched by the film and felt it connected to their lives.

The material from which The Children’s Hour is adapted, Lillian Hellman’s 1934 play of the same name, serves both as a starting and an endpoint for the book. Director William Wyler first adapted the “unadaptable” play in 1936, a few years after Hollywood’s Production Code was implemented. The resulting film, These Three, erases any textual evidence of the lesbianism depicted in the play, instead centering the plot on a love triangle between two women and a man.

Wyler, along with Hellman, adapted the play again in 1961 in an attempt to “get it right.” This meant the lesbianism of the play remained, including Martha’s (MacLaine) confession that she’s been in love with Karen (Hepburn) the whole time, and her subsequent suicide. 1961was the year the Production Code first started amending its guidelines, loosening the ban on sexual perversion thanks in large part to lobbying from producers of The Children’s Hour. Koresky uses these two films as bookends, exploring the 25 years between them and tracking how queer cinema changed – or didn’t change – during this period.

He aims to challenge the assumption that history is a linear march of progress, and effectively makes this point by delving into the films, filmmakers, and film censors that defined Hollywood’s Golden Era. The emergence of queerness in these films isn’t as straightforward as we might think. He argues that regardless of the literal text, both filmmakers and audiences imbued the films of this period with a “queer sensibility.” Moreover, these films were great “not merely in spite of the restrictions put on [them] but also because of them.”

Koresky suggests that far from being a strictly forbidden aspect of cinematic language, queerness was in fact central to the films of this era. Indeed, more so than in any other period, post-code films were always a negotiation between text and subtext, between seen and unseen, and this interplay defines how queerness seeped into an industry that forbade its existence. Engaging with complicated, potentially “negative” images of queerness, Koresky argues, can help “deepen our understanding of the present.”

We arrive in Hollywood in the 1930s. Though it was hardly recognizable as a descendant of Hellman’s play by the time it arrived in theaters, These Three was nonetheless a resounding hit. One could read its success as a confirmation that viewers don’t want to see queer stories, or that the rules of the Production Code smoothly aligned with cultural attitudes writ large. But that doesn’t tell the full story. First of all, Hellman’s play, which premiered only two years prior and featured a clearly identified lesbian character, was a smash hit. As for the film, though queerness was excised from the text, its ghostly presence remained. Attentively watching a film involves noting both what is there and what isn’t there, and every viewer brings their own phantoms to the table.

Any account of queerness in the Golden Age wouldn’t be complete without a consideration of Dorothy Arzner, the lesbian director who remained a respected (albeit with a patronizingly sexist caveat) member of Hollywood throughout her tenure there. Though Arzner’s lesbianism was an open secret, her films were far from explicitly queer. Still, Koresky argues that Arzner, whether consciously or subconsciously, steeped her films in queerness. “Each of these films is imbued with a sensuality that exists in the interplay between the women on-screen and those in the audience,” he writes, pointing to the relationship between the female leads in Dance, Girl, Dance and the lack of importance paid to the male love interest.

Alfred Hitchcock, on the other hand, was conscious and intentional about injecting queerness into his films. Hitchcock told Rope screenwriter Arthur Laurents that he hired him because he was gay and wanted him to bring his experiences – or his sensibility, if you will – to the film. (This wasn’t a stretch, as the movie was inspired by gay lovers Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb’s murder of a 14-year-old boy.) The resulting film, one of Hitchcock’s best, features two purposefully gay-coded murderers, doubling down on the director’s fascination with perversity. Rope got past the censors by taking the “text” of Leopold and Loeb’s queerness and making it subtext, though savvy viewers could see through the disguise.

In the chapter on Judy Garland, Koresky explores one of the most fascinating and oft misunderstood aspects of queer cinema culture. He shows his immense skill as a writer here, describing Garland’s exalted position in gay culture with exquisite clarity, wisdom, and depth. He begins by explaining why and how Garland became a gay icon, starting with the three categories defined by film scholar Richard Dyer. The first is ordinariness, particularly the dichotomy between Garland’s many “girl next door” roles and the tumultuous tragedy of her personal life. Second is adrogyny, best exemplified by the “tramp” character Garland appeared as on stage. Third is camp, which Koresky describes as “the knowing-self awareness in many of Garland’s roles, and the source of much of her distinct humor.”

Koresky adds a fourth category: hunger. This refers to the intense longing that sits at the core of many of her characters. This longing is most palpable in Garland’s songs, most notably “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” from The Wizard of Oz (a longtime gay classic), and “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas” from Meet Me in St. Louis. This leads Koresky to one of the most important points in the chapter, and indeed, in the entire book.

He dives into a question many have pondered over the years: why do gay people love musicals so much? His answers are illuminating. The form of the musical, in which characters oscillate from speaking to singing, creates this queer resonance. As the author puts it, “Musicals are formally driven by a feeling, which is that something inside has to come out.” In non-musicals, characters often find catharsis in physical violence or emotional conflict, but in musicals, catharsis emerges from “self-actualization, yearning, or confession,” usually in the form of a song.

The contrast between the intimate, confessional nature of the songs and the public-facing condition of the speaking portions represents the inside-outside conflict queer people face. In many cases, it's as if the singer is telling the audience a secret or revealing how they really feel. It’s a fairly literal embodiment of “code-switching.” The musical’s queer appeal, then, stems from its “sense that everyone has two identities – the more fantastical, seemingly artificial one being, ironically and excitingly, the more honest.” The musical’s departure from reality also reflects a departure from dominant social norms, such as heteronormativity. Koresky argues that Garland “both embodies and transcends the movie musical.” Her astounding voice gives the appearance of a larger-than-life, one-of-a-kind superstar, while her tragic personal life reminds us that she was as fragile as any of us.

Though this paradoxical interplay between public and private defines the musical, we can extrapolate it to cinema writ large. As Koresky suggests, these films resonate because of “a belief in cinema’s ability to animate the intangibility of life, in the movies’ desire to show the world beneath the one we can see.” While musicals depict the “world beneath” (or the world inside, as it were) in a literal sense through song, so do many of the non-musicals discussed in this book, but with a necessary amount of subtlety and sheen of plausible deniability.

The classic films that continue to reverberate through our culture are those that are complicated, ambiguous, and knotty in some way. For example, the 1956 film Tea and Sympathy follows Tom (John Kerr), a teenage boy outcast by his peers because he’s more interested in art and classical music than sports and lusting after girls. Though the film never confirms that Tom is gay (the play on which it is based is more explicit), director Vincente Minnelli imbues the film with gay meaning through composition, cinematography, and lighting.

The films of Tennessee Williams, one of the most revered and controversial playwrights of his time, also inspire several at times contradictory readings. Are his works homophobic and prejudiced against gay people, or are they revealing of a man’s fractured, self-lacerating psyche? Is his queerness synonymous with monstrosity, or does it indict the monster within us all? The variety of meanings extracted from these films constitutes their enduring quality. As Koresky writes, “Movies at their worst tell us what to think. Movies at their best still speak code.”

The release of The Children’s Hour in 1961 marks a turning point in the history of queer cinema, but not necessarily in the direction one might think. 1961 was the year the Production Code began to loosen its censorship rules, allowing depictions of “sex aberration” in film. (The code was eventually replaced by the MPAA rating system in 1968.) However, the removal of censorship didn’t make Hollywood movies more progressive or interesting. “When something is forbidden, it becomes desired; when something is accepted with a caveat, it becomes entrenched,” Koresky suggests.

Did The Children’s Hour usher in significant change within Hollywood? It’s hard to say. Despite Wyler and Hellman’s best intentions, the film didn’t resonate with viewers or critics and was considered a flop. Oddly, many critics took issue with the fact that the film assumed that homosexuality was still a topic that needed defending, thus positioning themselves as more liberal and refined than the text they were reviewing. In reality, attitudes about homosexuality hadn’t become particularly enlightened by 1961, and it would be many years before one could make the argument that queerness no longer needs defending (if one can make that argument at all).

Because The Children’s Hour was a financial failure, as were two subsequent gay offerings, Hollywood decided homosexuality wasn’t a topic worth spending money on, an opinion producers held for the rest of the decade. Ultimately, the 1960s proved to be a disappointing decade for queers on screen due to capitalism as much as social norms. Gay characters did appear on occasion, but they were not often sympathetic, and many followed in the footsteps of Martha’s tragic demise. While the 1961 film was meant to correct the omissions of These Three, it didn’t feel revolutionary or modern to contemporary viewers (though you could make the case for its radical bent).

The complicated response to the film and the fascinating story of its production indicate that a straightforward analysis of cinema history as directly reflective of political or social history isn’t sufficient. Looking at films of the past through our modern lens of representation doesn’t make sense either, as dichotomies like “good” and “bad” or “present” and “absent” fail to account for the many contradictions within these texts. Rather, we can point to the variable reception of such films as evidence of the negotiation between social attitudes, systemic limitations, and personal taste. The winds of change place these examples of queer cinema “in a historical double bind: distrusted and censored in their time for being too queer, dismissed years later for not being queer in the right ways.”

Though Sick and Dirty tracks the cinematic contributions of many talented and fascinating people, Koresky wants us to resist the draw of the hero narrative. “Whatever incremental change took place across the 25 years of filmmaking covered in these pages occurred not because of individual courage but because the profit-dependent capitalist machine of Hollywood reacts to a fickle and unpredictable marketplace,” he argues. It makes more sense to think of movies as “indications of cultural narratives” rather than messengers of radical ideas. Indeed, the changes that occurred during these 25 years are not the result of moviemakers becoming more socially progressive, but instead the industry learning to better integrate itself into the culture of which it is inherently a part.

A simplistic reading of the book’s argument might conclude that “it was capitalism all along.” And while that’s not untrue, Koresky relishes in exploring the complexity of these films – their production, their text, and their reception. The series of negotiations that produce the history Koresky covers don’t align perfectly with the notion of “regressive” or “progressive.” But it’s in those gaps and omissions that imagination is born. The (queer) viewer finds a way to carve out meaning and find belonging in images that are far from mirrors of their reality.

That sense of inspiration and imagination is what contemporary queer films and television lack, Koresky argues. Everything is right there on the surface, without much texture, tension, or ambiguity. Perhaps that’s one thing we can take from the Golden Era – the idea that the in-between or the almost-there is sometimes where great art lies. One could argue that popular images are more interesting when they don’t align with easily quantifiable metrics like representation; when they refract instead of reflect. Koresky’s book, in all its tautness and lucidity, encourages us to think outside the lines.