Exploring 'Lesbian Styles in Cinema'

A new book looks at lesbian clothing throughout film history

This is the Sunday Edition of Paging Dr. Lesbian. If you like this type of thing, subscribe, and share it with your friends. Upgrade your subscription for more, including weekly dispatches from the lesbian internet, monthly playlists, and a free sticker.

I’ll be doing another AMA (Ask Me Anything) in January (in celebration of five years of the newsletter!), and if you want to ask Dr. Lesbian any questions, you can ask them anonymously here or leave them in the comments below. I will answer everything unless you ask me something weird.

What is the difference between fashion and style? In their new book Lesbian Styles in Cinema, Vicki Karaminas and Judith Beyer distinguish between the two. “While fashion is a system of communication, it is primarily a commercial enterprise that relies on and creates fashion trends [...]” they write. On the other hand, “lesbian style is primarily concerned with dress codes and signs to communicate one’s identity, belonging, and sexuality.”

Lesbians have an interesting relationship to both style and fashion. Karaminas and Beyer note that in the 1960s, lesbians eschewed fashion because they thought it was patriarchal. Instead, they created a sort of ‘anti-fashion’ style that rejected normative notions of femininity and attractiveness. The types of clothes lesbians wear have changed over time, and as Karaminas and Beyer write, “There is no lesbian fashion; instead, there are lesbian styles.”

While lesbian styles have often functioned on the subcultural level rather than in the mainstream, Hollywood has played a significant part in shaping style in general and lesbian styles in particular. In Lesbian Styles in Cinema, Karaminas and Beyer track lesbian styles through film history and across genres to explore how lesbian style has shaped the appearance of lesbians on screen. Depictions of lesbian style in film illustrate the process of encoding and decoding, ie, the connection between the intention behind a series of images and how they’re read by audiences.

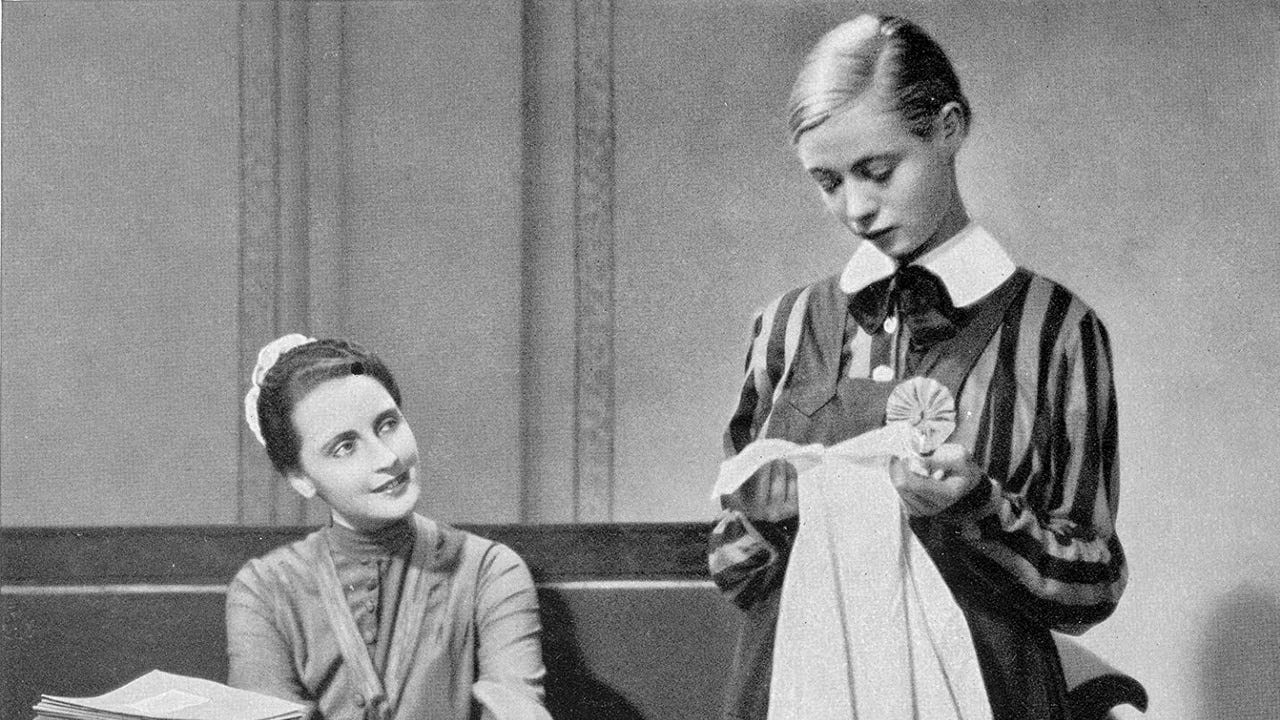

They begin with one of the most common genres of lesbian films: the coming-of-age drama. In the first half of the 20th century, boarding schools were the sites in which many of these stories came to life. Mädchen in Uniform, often considered the first explicitly lesbian film, uses the boarding school setting to explore ideas about gender, sexuality, and power. As film critic B. Ruby Rich writes, boarding schools function to teach girls how to become wives and mothers, but they are also “a sexual danger.” School uniforms, which embody the controlling arm of the patriarchy but also suggest an element of sexual transgression, express this tension.

In essence, the uniform serves as a “placeholder” until the girls are ready to fulfill their heterornamtive roles in society. Looked at another way, uniforms personify the closet. While they impose an appearance of sameness, they also act as a safe cover, concealing the truth of one’s difference. In Mädchen in Uniform, Manuela’s (Hertha Thiele) moment of lesbian self-disclosure, when she confesses her love for her teacher (Dorothea Wieck), occurs out of uniform, and in fact, while Manuela is dressed as a man for the school play. Style plays an important part in the boarding school drama, illustrating both the confines of heternomativey and how one might break free.

In lesbian coming-of-age films of the last few decades, lesbian styles follow recognizable patterns of difference. In movies such as The Incredibly True Adventure of Two Girls in Love, being butch, androgynous, or a tomboy is equivalent to being an out lesbian, while femininity is equated with being in the closet. In these instances, lesbian identity is communicated primarily through style, and there is an element of plausible deniability with more feminine characters, who could still be read as straight by some audiences. In more recent films, such as Booksmart and Unpregnant, lesbian characters use lesbian style, or anti-style, to communicate not only their sexual identities but their differences from their peers.

Discussing the new slate of lesbian films produced in the early 1990s, Rohna J. Berenstein wrote that “Lesbians are not born, they’re seduced.” Berenstein’s rather cheeky claim isn’t unfounded, and this kind of seduction is portrayed and played out through clothing. In Desert Hearts, Vivian (Helen Shaver) and Cay (Patricia Charbonneau) tease out this sartorial seduction. At the beginning of the film, Vivian wears stiff suits unsuited to the Nevada desert. As she gets to know Cay, whose appearance communicates her sapphic confidence, her clothing becomes more adventurous. “It is Vivian’s adoption of western clothing that indicates her willingness to take a risk and her openness to the possibility of lesbian sex,” Karaminas and Beyer write.

Carol similarly uses visual cues to indicate the (potential) presence of a lesbian relationship, though the dynamic is somewhat different. The scene where Carol (Cate Blanchett) “accidentally” leaves her gloves with Therese (Rooney Mara) acts as an early signifier of lesbian desire, as the glove, and hands more generally, are often associated with lesbian sex. Carol represents what Robert J. Corber calls a “cold war femme,” who is “defined by her dangerous desire.” Though her clothing is conservative, she has a sophistication that Therese lacks. On the other hand, Therese’s clothing communicates her youth, her working-class background, and, as Karaminas and Beyer put it, her “willingness to be sexually experimental.” As the pair drives further away from home, Carol’s style becomes more relaxed, and daring.

The most important element of this cinematic seduction is transformation. As Karaminas and Beyer write, “The transformation of the characters is traced through the garments that they wear.” This love-as-transformation has a special significance for lesbians and queer women. Indeed, entering into a lesbian relationship can also mean becoming a part of a new community and embodying a new identity; clothing plays a part in both instances.

Lesbian period dramas can “conjure up a time and place where love between women and their erotic realities are entirely possible and reflected in their clothing,” the authors write. Costumes can externalize ideas about the self that might have been invisible in a more repressive context. In Yorgos Lanthimos’ The Favourite, cross-dressing signifies danger. The bold, maniupalitve Sarah Churchill (Rachel Weisz) is the cross-dresser in question, and her “masculine attire exaggerates and illustrates her dominant character.”

Portrait of a Lady on Fire provides an opportunity to explore the world of color. The green dress is the most meaningful object and piece of clothing in the film, but as Karaminas and Beyer suggest, green can have multiple, contradictory meanings. While it symbolizes nature and health, it’s also linked to sexuality, fantasy, and toxicity. In fact, in the 18th century, a popular shade of green was composed of a chemical composition that was literally toxic. A green dress also figures prominently in Ammonite, and in both films, the green dress marks the characters’ lesbian desire and instigates action.

In Reaching for the Moon, the biopic about poet Elizabeth Bishop and the architect Lota de Macedo Soares, the color blue serves an important function. Blue fills the screen at the moments when their tumultous relationship feels full of life and brimming with potential. But blue isn’t a stable or grounded color. As Karaminas and Beyer write, “The things we most associate with the color blue, such as the sky, the sea, the horizon, are in fact apparitions.” Thus, while the blue period of their relationship is the most hopeful, it also reflects their love’s fleeting nature.

Though these films don’t directly reference such concepts, color-coding is an important part of both lesbian and gay culture. We might think of the handkerchief code, indicating preferred sexual practices, or the importance of violets and the color lavender. Though these practices exist outside the bounds of such films, Karaminas and Beyer suggest that “Within the constraints of the period drama, the historical setting and the constant threat of a strict and homophobic society, drawing on colour and its symbolism to communicate hidden desires seems plausible.”

The lesbian crime thriller presents lesbians and queer women in a dangerous light – for better and for worse. As Bryony White writes, lesbian killers are either “infantilised” or “deeply glamorous but vampish, often monstrous, red-lipstick-wearing femme fatales.” Within these films, but also in fiction in general, fashion itself is dangerous. In the collection If Looks Could Kill: Cinema’s Images of Fashion, Crime and Violence, Caroline Evans suggests that “fashion is treacherous, unstable, and volatile [and that] appearances are a snare that cannot be trusted, the devil’s vanishing trick.”

Nowhere is this more apparent than in the noir. That brings us to the masterpiece Bound, a crime thriller that functions as a lesbian film rather than a film that happens to be about lesbians – like many others in the genre. Violet (Jennifer Tilly), of course, represents the femme fatale, and embodies the dangerous, alluring sexuality of these archetypal characters. Her style codes her as villainous, though the narrative doesn’t portray her as such.

Corky (Gina Gershon), on the other hand, doesn’t represent the hard-boiled detective of noir, but rather the “composite screen rebel.” Her Perfecto leather jacket, first popularized by Marlon Brando in The Wild One, tells us as much. As Karaminas and Beyer put it, “Her garments not only heralded the anti-establishment hero, but the abstraction of the myth – or the ideal – is played out through the interactions between her body and her clothes.” Violet and Corky personify these iconographic figures through their clothing and subsequent gender presentation. Still, they subvert the presumed meaning of these images even as they embody them.

In the 1990s, a new lesbian style emerged on film. Karaminas and Beyer describe it as a “‘ladette’ lesbian style that included denim and leather, flannel shirts, massive boots, vests, and cropped utility gear such as cargo trousers and dungarees,” seen in films such as Go Fish and Bar Girls. This coincided with the so-called era of ‘lesbian chic.’ In more recent years, lesbian styles have become more fluid, which Karaminas and Beyer attribute to the “mainstreaming of the trans liberation movement.” New categories, like ‘chapstick lesbian’ and ‘futch,’ indicate how gendered categories have begun to blend, a development that has been represented in recent films.

Karaminas and Beyer characterize the changes that began in the 1990s as “marking a shift from derogatory stereotypes to trendy visibility.” As with most trends, this shift didn’t last. In the 2000s and 2010s, lesbianism was often conflated with ickiness, and the styles associated with lesbians were no longer seen as cool. But recently, we’ve seen another shift. Lesbian fashion was described (somewhat problematically) as a “sexy” new trend in 2022, and some have declared 2024 to be the ‘year of the lesbian.’

There’s no telling how long this upswing will last, and, as we’ve learned, there is a difference between lesbian fashion and style – one is trendy and commercial, and another communicates identity. Still, the book tracks some significant shifts in portrayals of lesbian style on the big screen. The biggest shift has been in the mainstreaming of lesbian styles. Lesbian dress codes are now better understood (or at least more visible) by the general public, in part due to their appearance on screen. While visibility isn’t synonymous with progress, nor is it always a net positive, this change has been meaningful for some, and has certainly changed many queer folks’ relationship to the movies.

What are your favorite lesbian costumes in film? Let me know in the comments below.