Cowgirl Take Me Away

How ‘Desert Hearts’ Remakes the Western In Its Own Image

This is the Sunday Edition of Paging Dr. Lesbian. If you like this type of thing, subscribe, and share it with your friends!

What makes a western a western? According to book editor Shawn Coyne, “The Western story concerns the role of the individual in a mass society. Is the self-reliant individual dangerous to order or necessary to defend the powerless?” The western grapples with the push and pull between independence and connection, between the individual and the collective. Westerns are also about changing ideas – the cowboy is old school, and must confront new schools of thought that threaten his way of life.

As Robert Wood puts it, “The argument can be made that Western narratives are one cultural expression of ‘anachronism fiction.’ That is, fiction which focuses on characters or ideas that are in conflict with their apparent successors.” These anachronisms are represented by the various archetypal characters in a western, with these dramas acted out in the landscape of the frontier. While the western hero in earlier westerns – think John Wayne – were traditionalists not interested in disrupting society, later westerns, such as those made in the 1960s, often featured characters who would be better described as anti-heroes. Anachronism was still the name of the game, but the growing counterculture movement had changed the positions of the players.

Certainly, these conflicts are rife with the possibility for queer text and subtext, right? We can surely think of some examples of this. Writing in the Washington Post, Stephen Hunter suggests that the western is a genre that has been “saddled with subtext.” Hunter discusses Red River (1948), Bend of the River (1952), and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969), which, as he describes it, “featured two of the most beautiful men alive on the lam in the wilderness, far from the eyes of propriety and the moderating influence of civilization, and in an outdoors that was really a gigantic locker room.”

Obviously, the most prominent example of a gay western is Brokeback Mountain (2005), which follows two cowboys (actually shepherds, if we’re going to be pedantic about it) who fall in love. But there have always been undertones of male queerness in cowboy culture – think Ned Sublette’s 1981 song "Cowboys Are Frequently, Secretly Fond of Each Other," which was famously covered by Willie Nelson in 2006 (and is arguably the first mainstream gay country song). More recently, there was Jane Campion’s Power of the Dog, which masterfully explores masculinity and queerness in early 20th-century America. And of course, we can’t overlook Lil Nas X, who has strategically (and joyfully!) reworked the iconography of the cowboy in his own gay, black image.

This is all well and good, you might be thinking to yourself, but where are the women in this picture? There was Gus Van Sant’s critically panned1 Even Cowgirls Get the Blues in 1993, but I don’t think anyone wants to claim that film for the cowgirls or for the lesbians. This is where Desert Hearts, first released in 1985, comes in.

The 1980s was a strange time for the western. Mostly, the decade saw the decline of the western as an American film genre even as Ronald Reagan, who had fashioned himself as an old-school cowboy, rose to power. Most notoriously, 1980 saw the release of Heaven’s Gate, a big-budget flop that is said to have tanked the independent production company United Artists (originally founded by Charlie Chaplin) and put a decisive end to the New American Cinema movement of the 1970s. As a matter of fact, there were very few westerns released from the year 1980 to 2003.

It might seem odd then that Desert Hearts, which utilizes a lot of the western’s iconography and themes, came out in such a barren decade. But, as it turns out, the film is something of a miracle itself. Directed by Donna Deitch, Desert Hearts is set in 1959 and follows Vivian (the magnificent Helen Shaver), a 35-year-old English professor at Columbia who has traveled to Reno to get a divorce. While staying at a ranch run by Francis (Audra Lindley), Vivian meets young Cay (Patricia Charbonneau in her first-ever film role), a free-spirited artist who’s not afraid to share her predilection for women. Obviously, the two women fall in love, and the experience is transformative for both of them, forever altering how they see themselves and their place in the world.

For Deitch,2 it was an uphill battle to get the film made. Based on the novel Desert of the Heart by Jane Rule, Deitch wrote the script for the film and then spent two and a half years raising money for production, mostly from private donors. Casting wasn’t easy, either – many actresses declined to audition for the film because of its subject matter. Even once the film had wrapped, they still didn’t have the money for post-production, and Deitch had to sell her house in order to complete it. But, somehow the film did eventually get made and was shown in theaters across the country, and, according to Deitch, nearly broke the house record for ticket sales at one cinema in New York.

But is Desert Hearts even a western? At the very least, it uses classic western iconography in a new way, and, at most, it remakes the western story in its own lesbian image. Deitch had a specific idea in mind for how she wanted the film to look, and, visually, it’s one of the most stunning depictions of a western landscape released in the whole decade. The director of photography on the film was Robert Elswit – most well known for working with Paul Thomas Anderson on films like There Will Be Blood – and Deitch gave him a book entitled Vanishing Breed: Photographs of the Cowboy and the West, as a visual reference for the project. The film’s editor, Robert Estrin, was the editor for Terrance Malick’s Badlands, another low-budget film that features a couple on the road out west.

Music was also extremely important to Deitch, who spent $250,000 of the $1 million budget on the soundtrack. Artists like Patsy Cline, Kitty Wells, and Elvis Presley make up the soundtrack for the film, contributing in a huge way to the 1950s western milieu in which the characters inhabit.

At its core, of course, Desert Hearts is a love story, but it uses western themes and visual touchstones in order to illustrate the narrative in a way that's both familiar and novel to audiences. Romances, as well as westerns, find their heroes fighting outside forces and overcoming roadblocks to reach their goals. In a romance, this goal is the consummation of a love story. In a western, the goal is freedom. In Desert Hearts, these two objectives are intimately connected.

In her chapter in the 1995 book Immortal, Invisible: Lesbians and the Moving Image, Jackie Stacey describes lesbian films prior to Desert Hearts as “lesbian disaster movies.” As Stacey points out, romances are all about overcoming obstacles in order to achieve happiness, and, in every lesbian film prior to this one, such obstacles were found to be insurmountable. As Stacey puts it, “The legacy which Desert Hearts inherited, then, as a lesbian romance narrative, presented something of a double bind: the traditional forms of dramatic interest and emotional suspense in this genre had been produced through obstacles which reinforced definitions of lesbianism as a negative category.” This meant that depictions of lesbian love in the past had been almost exclusively tragic, but also that, in subverting normative conventions of dramatic conflict, some audiences were left wondering why the film didn’t have more narrative tension.

Somewhat surprisingly, the obstacles Vivian and Cay face in Desert Hearts are not all that imposing, and each one is quickly chipped away at as they embark on their journey together. Francis (Cay’s pseudo-mother-in-law) is the biggest external threat, and, while they must face her down at one point, the fight fizzles out rather quickly. Indeed, the biggest threat to their happy ending is Vivian’s own internalized shame and her fear of being truly free. Like Portrait of a Lady on Fire, the film often eschews typical narrative conflicts, instead focusing on the more symbolic questions of freedom and self-determination to drive the plot forward. Such ideas, of course, have often been the provenance of cowboys and outlaws. As symbolized by the world of casinos in which Cay and Vivian inhabit, the women must take a chance – gamble, if you will – on love.

Both visually and thematically, Desert Hearts pulls from the history of the American western. Location is important here. Vivian and Cay represent the east and the west – the contours of their love story are written into the contours of the land and the spaces they occupy. As Stacey suggests, “The desert functions as a transformative space, a place where the miles and miles of wide-open landscape can absorb the past and new possibilities can be found. Mythically, it is the place of adventure and self-determination.” While Reno in 1959 is not quite the “wild west” of American myth, it still functions in this way for Vivian, who ventures away from “civilization” and winds up finding herself along the way.

The contrast between Vivian and Cay is baked into the landscape, too. Cay is comfortable outdoors, riding horses and driving down the freeway at high speeds. (They never actually ride horses in the film – during the scene where they’re meant to be going riding, the horses are walking beside them. Deitch has said it’s because she wanted the actors’ faces and the horses' faces to be in the same frame.) Vivian, on the other hand, who has not brought proper clothing for the desert, prefers the indoors, where her pesky emotions and hidden desires can be better contained.

Their first kiss represents this dichotomy symbolically (and beautifully). After driving to the lake together after a party, Vivian and Cay get caught in the rain. Vivian gets in the car, and Cay stays outside, asking Vivian to roll down the car window. They kiss like this, with Vivian inside the safety of the car and Cay reaching her head inside to capture Vivian’s lips with her own. This image of containment is repeated throughout the film, as the characters are often captured within frames (such as doorways or windows), symbolically illustrating the distinction between confinement and freedom – yet another theme of the western.

If the characters in Desert Hearts inhabit the world of a western then who, you might ask is the cowboy? The obvious answer, of course, is Cay. She lives alone, surrounded by vast wilderness, she rides horses, and she cares not about society’s expectations of her. But, to put it more precisely, the western archetype Cay represents in the film is that of the outlaw. Certainly, there is an overlap between the cowboy and the outlaw, but the biggest distinction between the two is the notion of tradition. While cowboys are, for the most part, morally traditional, outlaws tend to buck tradition, or, at the very least, not put much stock in it.

This dichotomy is realized in the dynamic between Cay and Vivian. After their transformative first night (and day) together as lovers, Vivian struggles to adjust to the new reality she finds herself in upon leaving the hotel they’ve been holed up in. Vivian becomes upset when men at a bar start noticing them and she flees, starting an argument with Cay about the seemingly incompatible ways they each live their lives. When Vivian voices her discomfort about being out in public with Cay, Cay tells her, “Listen, you’re just visiting the way I live.” This is where their different roles in the world butt heads – Cay is not willing to sacrifice her way of life, while Vivian is not (yet) comfortable changing hers.

Moments later, when Vivian bitterly (and perhaps jealously) comments on the confidence with which Cay moves about the world, Cay responds, “I don’t act that way to change the world, I act that way so the world won’t change me.” Herein lies the heart of Cay’s outlaw mentality. She’s not interested in progress in a collectivist sense (something neither the cowboy nor the outlaw cares much about), but instead is focused on living out her own truth, no matter the consequences. She refuses to live against her own grain, finding freedom in the desert landscape and the wide-open spaces of the west. And if Cay is the outlaw, then that makes Vivian the civilizing force of society, and in this case, the east. But, we must not forget this is a love story at its heart, and, as Deitch sees it, these two forces need not be diametrically opposed forever.

So how can these two women compromise? How do they find common ground, or a common language? The answer, of course, is fashion. Oh, the clothes! We have to talk about the clothes. The costume design in Desert Hearts is stunning (perhaps the best filmic lesbian fashion moment of all time), and this is no accident. According to Deitch, each piece of clothing from the film is actually from the 1950s, chosen and styled by costume designer Linda Bass. (The dress Vivian wears in the lawyer’s office is actually a design created by Deitch’s mother in the 1950s that was remade especially for the film.)

In one short but important scene, Cay takes Vivian shopping in a country & western store in order to update Vivian’s western wardrobe. While Vivian initially enters the film wearing a very proper dress and hat, she gradually begins to appear more casual as the film goes on, eventually going so far as to wear a western shirt and jeans. Cay, on the other hand, always looks like she fits right in in the desert, casual and at home in her body in a way Vivian is not.

The aforementioned shopping scene is important because it represents, as Deitch puts it, an example of “taking on the wardrobe of the other.” The fashion of the film is significant in that it helps define the time and place, and it also develops the relationship between the characters. Clothing has always been important to queer and trans people, as it can help one to feel comfortable in or literally “try on” a new identity. Having someone to help you with this transformation – as Cay does with Vivian – can be a formative experience, whether this relationship is explicitly romantic or not.

As the film goes on, Vivian discovers a new physicality, much of which has to do with her new attire. Even at the end of the film, when she is wearing the same outfit that she wore when she first arrived in Nevada, she wears it differently. She’s not wearing her hat, there are a few stray curls peeking out of her updo, and she looks, to put it simply, less buttoned-up than she did at the start of the film.

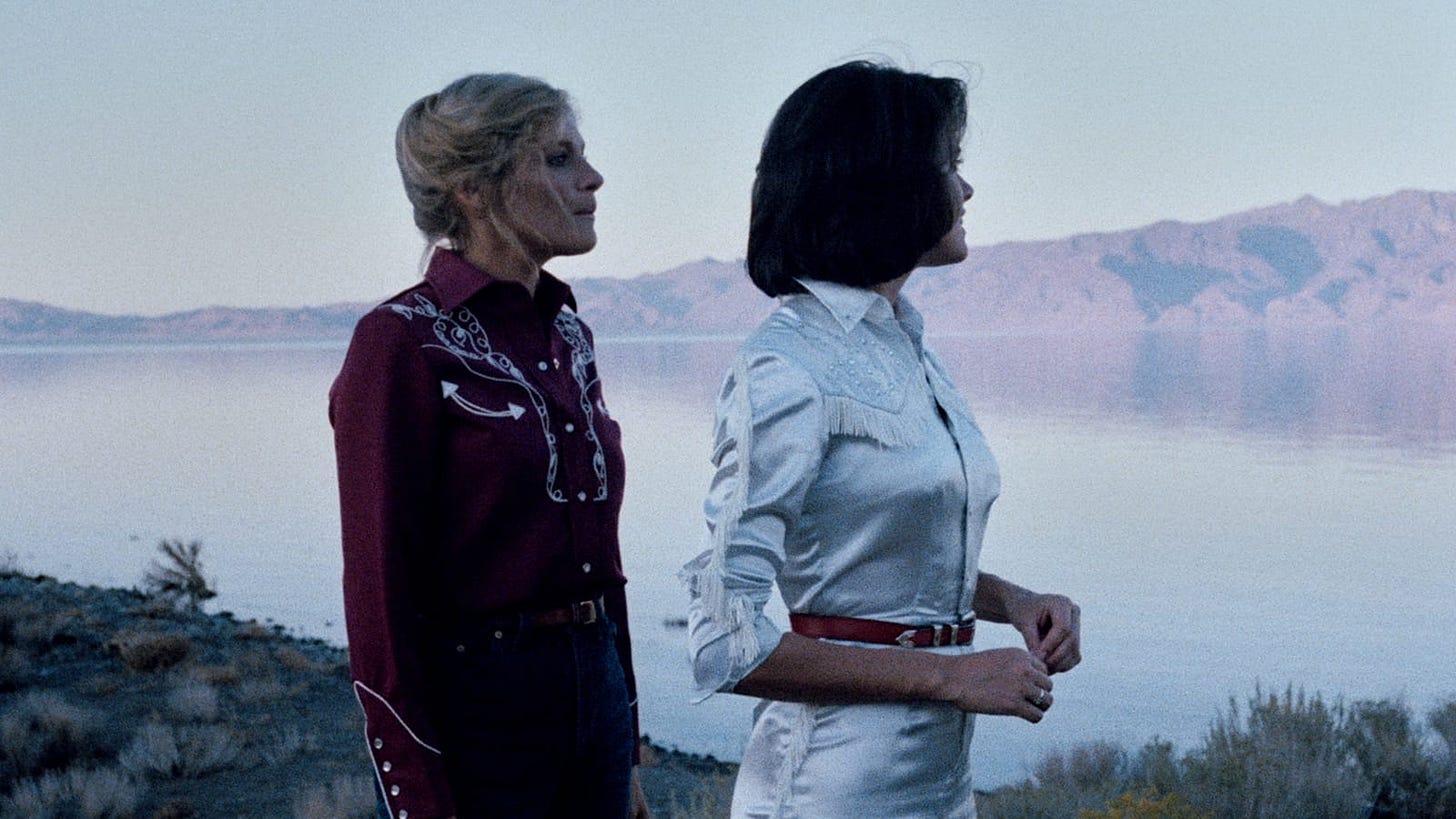

Symbolic meaning aside, there is also the fact that the clothing in the film adds to its sumptuous look and feel. In one scene, when Cay and Vivian are attending Silver's (Andra Akers) engagement party, Cay wears a silky white jumpsuit with red cowboy boots and Vivian matches her in a red western shirt and jeans. Cay’s outfit is a rhinestone cowboy moment for the lesbian set, and, as Deitch puts it, “She’s meant to look more like Elvis than he could ever look.” (It helps that Elvis is also on the soundtrack.) These are the outfits they are wearing when they share their first kiss, each look defining the characters’ positions in that moment. Cay, a confident ladies (wo)man, and Vivian, becoming more in tune with the west with each waking minute.

So, is Desert Hearts a western? Can a western be a film about two women in the American west navigating the muddy waters of love and freedom? Can it be about driving down a barren highway in the middle of a rainstorm? Can it be about a lesbian outlaw who looks a little bit like Elvis? Purists would say no, but you can’t please everyone. If anything, the legacy of Desert Hearts is how it took the classical form of a love story and the popular iconography of a western and made them into something that hadn’t been seen before.

While Desert Hearts was not received with total admiration by every viewer – especially from the New Queer Cinema and queer theory-tinged 1990s milieu that Stacey is writing from – it nonetheless has left an important legacy within lesbian and queer film culture. As lesbian film scholar B. Ruby Rich notes, Desert Hearts came at a risky time. “In the postmodernist ‘80s, it is risky to be romantic, unfashionable to be direct, and downright retrograde to be lesbian.” And yet, Desert Hearts did (and is) all of these things, all at once. Moreover, the fact that this film was made in the 1980s – the decade that saw the death of the western as an American film genre – makes its presence even more exceptional.

Looking back, Desert Hearts might not seem all that revolutionary to our modern eyes. But, when considering the effort it took to get made, and the fact that it was even made at all, one’s perspective on the topic is liable to shift. What’s more, while modern audiences might not consider the themes of the film particularly novel – cross-cultural differences, an older and a younger woman, a transformative, romantic love scene – in many ways, Desert Hearts was the blueprint for these tropes. We joke about lesbian period pieces today, but a film like Carol owes a lot to Desert Hearts, which was released 30 years prior and without the support of a big studio or a well-known director.

An epic love story, a lesbian period piece, and a western all wrapped in one, Desert Hearts is a miracle of a film – just like Cay, our lesbian outlaw and rhinestone cowgirl. Cue The Chicks.

Wow, very thorough analysis. Great read.