10 Movies To Watch If You Love Carol

On falling in love, out of time

This is the Sunday Edition of Paging Dr. Lesbian. If you like this type of thing, subscribe, and share it with your friends. Upgrade your subscription for more – I could really use your support! It’s hard out here in journalism right now. This post is too long for email, so read on-site or in the app.

Within the popular lesbian imaginary, there are few films as beloved as Todd Hayne’s 2015 picture Carol. Swaths of sapphics make it their ritual to watch the movie every year around the holidays, and it has become something of a cultural touchstone within our community. I’m not going to deny the film’s significance (or indeed, its merit as a piece of art), though I do think there are other queer films worthy of serious/fervent consideration.

Instead, because I know many of you reading this are probably fans of the film – and even if you aren’t, I’d wager you still might enjoy some of these picks – I’ve decided to compile a list of films that I think would work well as companion pieces of a sort. I know I’m not the only one who’s constantly looking for new films to watch, so I hope you might add some of these to the queue.1

Some of the following movies are thematically similar to Carol – star-crossed romance, coming-of-age narratives, and the like – while others have stylistic connections or authorship links. Carol is, of course, a ‘50s romance, which has its own evocative connotations. When we think of the decade we often think of sexual and social repression as well as the refined fashions and styles of the day. Such an environment invariably influences the kind of love stories that are told during and about this period, something this list certainly illustrates. There is an overall theme of longing – longing to be free of something, longing to be close to someone – in this catalog that I think ties everything together nicely. Some of these movies are queer, while others aren’t, but, as much as I like to often tie it to queerness, longing seems to be a pretty universal feeling. Time to yearn!

Brief Encounter (1945)

Any list of this sort would be incomplete without this first movie, which has had more of an obvious influence on Carol than perhaps any other film. Brief Encounter is a 1945 film directed by British filmmaker David Lean, a director who is mostly known for making epics like The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) and Lawrence of Arabia (1962). In contrast, Brief Encounter is the opposite of an epic, and in fact, takes place over only a few short weeks in just three or four humble locations.

The magnificent Celia Johnson plays Laura, a suburban housewife who has a chance encounter with Doctor Alec (Trevor Howard) at a train station. They soon find themselves falling in love, but with spouses and children of their own, they find it difficult to imagine a future together. Thus, while it is a romance, it is a rather melancholic one, as the circumstances are less-than-ideal. As Laura puts it in one of the film’s most arresting lines, “I didn't think such violent things could happen to ordinary people.”

For Carol fans, the connection between the two films is quite clear. As in Carol, Brief Encounter begins with the penultimate scene of the film, as Laura and Alec prepare to say their goodbye but are rudely interrupted by an acquaintance. When we return to this scene in its proper place, it is devastating. When Alec leaves with a hand on Laura’s shoulder – sound familiar? – the subtle action speaks volumes that the two characters can no longer convey in words. It’s a masterclass in ordinary amour, which makes it all the more affecting to behold.

Olivia (1951)

While the 1950s are synonymous with repression and the forceful imposition of normalcy, there were numerous films in the era that defied or complicated these norms. Case in point: the 1951 film Olivia, which is one of the queerest films of the decade. Directed by French filmmaker Jacqueline Audry and based on a 1950 novel by Dorothy Bussy, the film is set in the late 1800s and follows Olivia (Marie-Claire Olivia), an English teenager who attends a finishing school in France.

Olivia encounters a rather strange situation at the school. All of the pupils are either devoted to the headmistress, Mlle Julie (Edwige Feuillère), or her rival, Mlle Cara (Simone Simon), who is completely obsessed with Julie. Mlle Cara takes an immediate interest in Olivia, but Olivia quickly falls in love with the beautiful Mlle Julie. Things become more complicated with the arrival of Laura (Nadine Olivier), who was once Mlle Julie's favorite pupil.

This synopsis might not give you an accurate description of just how gay this movie is, but trust me, it is G-A-Y. Literally every pupil at the school is a huge lesbian, and Mlle Julie and Mlle Cara seem to be playing some sort of psychosexual sapphic game with one another. There is even a scene where Mlle Julie comes in and kisses Olivia’s eyelids while she’s in bed. It’s absolutely a hallmark of lesbian filmmaking and also a knotty, compelling coming-of-age story. It would pair well with Mädchen in Uniform, another groundbreaking lesbian boarding school film from the 1930s, which also has an incredible goodnight kiss scene.

Hiroshima mon amour (1959)

An early entry in the French New Wave movement, Alain Resnais’ Hiroshima mon amour is a masterpiece of romantic filmmaking. Set in Hiroshima after WWII, the film follows a French actress, Elle (Emmanuelle Riva), who strikes up an acquaintance with Lui (Eji Okada), a Japanese architect. The two have an affair, but much of their time together is spent having profound conversations about the story of their lives thus far.

Exquisitely shot in black and white, the film is a poetic examination of the intertwining of personal and political histories and the horrors and promises of memory. Interestingly enough, the lesbian film that Hiroshima mon amour has the closest connection to is not Carol, but actually, a 1983 film called Lianna, which I wrote about recently. The love scene in Lianna is scored with dialogue from Hiroshima mon amour, a film that is clearly synonymous with European refinement and cool.

The 16-minute monologue that begins the movie is perhaps the most exquisite opening ever captured on film. Written by French feminist Marguerite Duras, it's a masterclass of a screenplay that transcends the category of romance entirely.

The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964)

French director Jacques Demy is a filmmaker like no other, and The Umbrellas of Cherbourg is one of his essential masterworks. More of an opera than a musical – every piece of dialogue is sung – Umbrellas is a bittersweet romance filled with stunning colors and lilting melodies. The resplendent Catherine Deneuve plays Geneviève, a young woman who works in her mother’s umbrella shop. In the late 1950s, she meets Guy (Nino Castelnuovo), a mechanic. Geneviève and Guy fall in love and make plans for the future, but their happiness is interrupted when Guy is sent to fight in the Algerian War.

As in Carol, each shot in the film is composed perfectly and every colorful scene is a delight to behold. The sing-talking style of the music might take some getting used to, but if you haven’t seen a Demy film before, you’re in for a treat. Fair warning: The Umbrellas of Cherbourg isn’t exactly a happy film, so if you’re looking for a technicolor musical that’s a little more cheerful, check out Demy’s follow-up film, The Young Girls of Rochefort, which also stars Deneuve.

Desert Hearts (1985)

If you’re a long-time subscriber of this newsletter, you may recall that I have a lot of affection for the film Desert Hearts, but its merit bears repeating here. If you’re a fan of Carol, you may notice that the two films have much in common. Directed by Donna Deitch, Desert Hearts was one of the first lesbian films to be distributed nationally and certainly one of the first to be directed by a lesbian. Helen Shaver (giving one of the all-time greatest performances of an uptight lesbian, in my opinion) plays Vivian Bell, a professor at Columbia who travels to Reno to get a divorce in 1959. While staying at a ranch outside of town, Vivian meets Cay (Patricia Charbonneau), a free-spirited young artist. It’s a love story between a cowgirl and an intellectual, if you will.

Vivian is a very buttoned-up woman who needs to learn to loosen up a little, and Cay is exactly the right person for the job. As in Carol, there is an age gap between the two women, but in this case, the younger of the two is the one driving much of the action. The film is shot by frequent Paul Thomas Anderson collaborator Robert Elswit, who captures the evocative desert landscapes as if they were paintings. There are also plenty of sequences of the women driving around in a midcentury car, for all you Carol-heads out there. And, if that’s not enough to strike your fancy, the film features some of the best fashion in any lesbian film ever (Therese’s silly little hat notwithstanding), and the cowgirl looks are to die for.

The Talented Mr. Ripley (1999)

Carol is based on Patricia Highsmith’s novel The Price of Salt, which was originally published in 1952. Highsmith was, by most accounts, not a good person, but she was certainly a talented writer. In addition to Strangers on a Train, which was adapted into a Hitchcock film, Highsmith’s most well-known work is The Talented Mr. Ripley, which was made into a film directed by Anthony Minghella in 1999. Set in the late 50s, the film stars Matt Damon as Tom Ripley, a clever grifter who gets in with the upper-crust crowd by pretending to be a man of privilege. Ripley meets Dickie (Jude Law), a Princeton grad living with his girlfriend, Marge (Gwenyth Paltrow) in Italy.

Tom becomes a con man of sorts, impersonating Dickie and living a life of luxury. He meets an American socialite (Cate Blanchett), whom he befriends. Things get more and more dangerous for Ripley, and he is forced to act aggressively in order to keep up pretenses. In addition to a young Blanchett, the film also stars the dearly departed Phillip Seymour Hoffman as Dickie’s slimy and hilarious friend, Freddie.

I should also note that the film is quite gay, and if you’re looking for a movie where everyone looks beautiful and acts queer (in more ways than one), you should check this one out. Though Ripley is probably a psychopath and doesn’t seem to actually care for the men in his life, he is certainly attracted to them in an ego-affirming sense, which makes for a rich tapestry of emotional pitfalls.

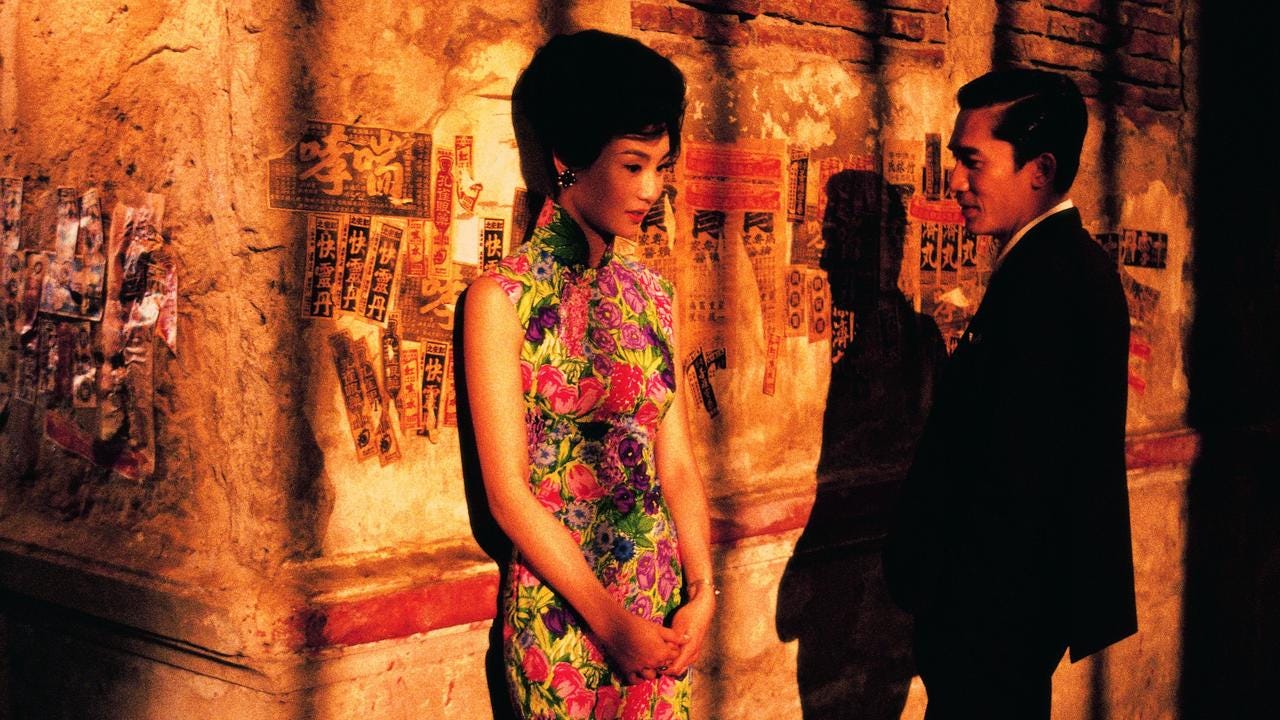

In The Mood For Love (2000)

One of the most delightful aspects of Carol is how beautifully composed it is. Every shot is framed in the most aesthetically pleasing way possible, as the evocative colors and elegant cinematography bolster the emotional world of the film. If you’re looking for a film that’s similarly vivid, feast your eyes on In The Mood For Love, Wong Kar-wai’s multicolored romance.

Set in Hong Kong in 1962, the film follows Chow (Tony Leung), a journalist, and Su (Maggie Cheung), a secretary, who rent rooms in neighboring apartments. Their respective spouses are away frequently for work, and when they learn their partners are having an affair, they begin to grow close. They start imagining what their spouses might do together, role-playing an affair until they find themselves falling in love for real. Their affair is constrained, and delicate, and always on the brink of becoming something more. As in Carol, even the briefest of touches between the two characters are laden with meaning, and much remains unspoken between the two.

It’s also undoubtedly one of the most beautifully hued films of all time, and its stunning primary colors speak even louder than the characters do. It’s a slow burn that glows with quiet intensity and restraint.

Far From Heaven (2002)

Todd Haynes is a diversified filmmaker, being the brains behind films as seemingly disparate as Safe, Velvet Goldmine, and Dark Waters. While he certainly has style, the form that this takes often varies from film to film. In regards to Carol, the Todd Haynes film that it has most in common with is probably Far From Heaven, his golden age drama starring Julianne Moore. Like Carol, the 1950s-set film sprinkles its muted color palette with thoughtfully-placed pops of color, and uses the backdrop of the decade to illustrate its themes of sexual and social repression.

But, unlike Carol, which is more of an understated romantic drama – though it transforms into a noir somewhere past the halfway mark – Far From Heaven is very much a melodrama. Haynes modeled the film on the works of Douglas Sirk, a director known for 1950s melodramas like All The Heaven Allows and Written On The Wind. Dismissed as mushy “women’s pictures” at the time, Sirk’s films have since been regarded as masterpieces.

As in many of Sirk’s films, Far From Heaven depicts characters who are trapped by their circumstances. Moore plays Cathy, a housewife2 in suburban Connecticut. She learns that her husband, Frank (Dennis Quaid) is gay and their relationship becomes strained. Meanwhile, Cathy meets her new gardener, Raymond (Dennis Haysbert), and they fall in love. Frank and Cathy’s marriage deteriorates even further, and Cathy and Raymond's chaste affair threatens to destroy both of their lives. It’s an artfully rendered drama that patiently works to earn its heartache.

Reaching For The Moon (2013)

So far, we’ve discussed two lesbian romances set in the 1950s, and there’s a third one we need to add to the list. Reaching For The Moon is based on a true story of lesbian love. Miranda Otto plays Elisabeth Bishop, an American poet who travels to Rio de Janeiro to visit her friend Mary (Tracy Middendorf). While there, Elisabeth meets Mary’s partner, the famed Brazilian architect Lota de Macedo Soares (Glória Pires). The shy Elisabeth and the dashing Lota take a liking to one another, and Lota pursues Elisabeth even though she’s in a relationship with her friend, believing that they can make it work.

Bishop intended to spend only a few days in Rio but wound up staying for nearly twenty years, writing her Pulitzer Prize-winning work there. Lota, on the other hand, was asked by the Governor personally to design a public park in the city during this period. Though loving, their relationship was quite tumultuous, and their problems were exacerbated by Bishop’s alcoholism and Lota’s headstrong nature.

It’s an amazing piece of history, but it’s certainly not a happy-go-lucky love story. If you’re especially sensitive to depictions of mental health struggles or suicidal ideation, you might want to skip this one. But, if you’re looking for a complicated portrait of a celebrated lesbian poet – filled with recitations of said poems – then you should seek it out.

And Then We Danced (2019)

I’m a sucker for coming-of-age stories – Carol is one, I’d argue – and it’s even more exciting when they’re gay. One of the best gay coming-of-age films I’ve seen in years is And Then We Danced, a Georgian film released in 2019. Merab (Levan Gelbakhiani) is a young dancer who is training at the National Georgian Ensemble. Merab has been working hard for a spot in the main ensemble, and his focus is interrupted by the arrival of a new dancer, Irakli (Bachi Valishvili).

Irakli has a cocky attitude and Merab is initially jealous of his natural talent and worried he will beat him out for the coveted spot. Eventually, however, the two men become close and develop a romantic relationship. When the burdens of culture and familial obligation begin to tear them apart, Merab must decide if he is strong enough to live the life he knows he was meant to live or simply abide by tradition.

Kind of like a mashup of Flashdance and Black Swan, the film is a beautifully rendered portrait of the push and pull between personal identity and cultural expectations. Merab’s journey to self-empowerment is an emotional rollercoaster and his final, declarative dance – see the Flashdance connection – is both tear and cheer-worthy.

Let me know if you like reccomendation lists like this and if you would be interested in me writing more.

If you’re looking for a film where Julianne Moore plays a ‘50s housewife who is also gay, check out The Hours, which I think is quite underrated.

You could write every week about Desert Hearts and I’d cheer! 😹

Also, you’re right: The Hours is underrated. You know you have a great film when Meryl Streep gives the least interesting performance — and she’s still good!

Amazing as always! PS: and that reminds me: I need to re-watch Carol, lol (for the gazillionth time)