'Stick It' To The Man

The Movie That Taught Us Everything We Need To Know About Queerness and Feminism

This is the Sunday Edition of Paging Dr. Lesbian. If you like this type of thing, subscribe, and share it with your friends. A paid subscription gets you more writing from me and will help me keep this newsletter afloat. Consider going paid!

If you were born in the 1990s like me, you may remember the film I’m about to discuss, despite the fact that it came out in the year 2006 – a veritable treasure trove for teen movies – and, on the surface, doesn’t seem like the kind of film that would stand the test of time. I only recall ever watching the film once as a child, probably at the age of 11 or 12, but it’s been stuck in my mind ever since, even more so than Bring It On (which, to be fair, I only watched years later).

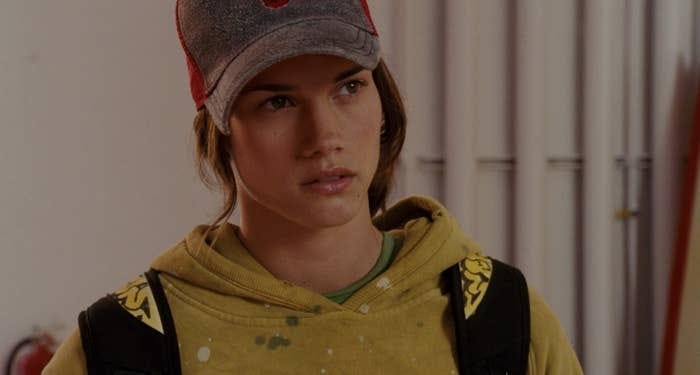

Starring a then-unknown Canadian actress named Missy Peregrym, Stick It was directed by Jessica Bendinger, who also wrote Bring It On (as well as the teen classic Aquamarine). Set in the draconian world of competitive gymnastics, Stick It is ostensibly a film about female empowerment and solidarity, but the ways in which gender is portrayed in the film has also endeared it to lesbian and sapphic audiences over the years. If the number of times I have seen that gif of Missy Peregrym getting out of that ice bath is any indication, the film has certainly had an effect on the community.

2006, the year of Stick It’s release, was a huge year for teen movies. The auspicious year saw the release of films like Step Up, She’s The Man, John Tucker Must Die, and High School Musical. When you think about it, so many of these films are about gendered expectations and women (and men) breaking free of them, and Stick It is no exception. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Stick It received only lukewarm reviews upon its release that year, and, as it stands, only has a 32% on Rotten Tomatoes. But, it’s become something of a cult classic, and cast members say it’s by far the thing they get recognized for the most.

Clearly, something about this film still resonates today, and I think much of it has to do with the film’s feminist and queer themes. The first thing we need to discuss is Haley’s (Peregrym) gender. At the start of the movie, we see three figures on BMX bikes and skateboards – presumably all boys – riding around an abandoned construction site. One of the boys accidentally crashes through the window of the house being built on the lot and – surprise! – that boy is actually a girl.

This is a classic movie trope that’s meant to indicate the gender deviance of a character – clearly, Haley is not the girl-next-door type we’re used to seeing in teen movies. Her two best friends are boys, which also emphasizes her queer relationship to gender (and perhaps sexuality). Gender deviance in women’s sports is actually a theme that is common in mainstream films. She’s The Man is another film about gender transgression and sports, as is the similarly queer Bend It Like Beckham (perhaps the most famous “lesbian” sports movie of the 2000s.) Gender nonconformity tends to be baked into movies about women’s sports because such activities are automatically seen as outside the norms of (hetero)femininity. But, unlike many other sports movies – She’s The Man, for example – Haley doesn’t have to abandon her gender deviance or embrace heterosexuality in Stick It in order to succeed or complete her story arc.

Gender deviance is almost always assumed to be connected to sexual deviance. Certainly, this assumption is not necessarily a bad thing, especially when it's queer people themselves reading this into a given text. The fact that many viewers have read Haley as gay is also indicative of the fact that there were so few masculine-of-center or queer women on screen at this time, so Haley was clearly filling a void. And, the fact that Haley has no male love interest in the film – something the director had to fight for – further legitimates this reading of her character. Whether or not Haley was meant to be read this way is, for the most part, irrelevant.

Gender deviance aside, we also can’t deny the role thirst has played in the queer fandom surrounding this film. Let’s circle back to the famous ice bath scene. This image has permeated the screens of the post-Stick It generation for years on end, and I doubt even Missy Peregrym knows the effect her abs have had on a generation of women and queer people. The scene is also so exhilarating because examples of women’s strength in such a physical and visceral way are so rarely seen on film. (In case you were wondering – yes those were Peregrym’s real abs and yes that was real ice she was bathing in.)

Moreover, women’s sports have always been celebrated vocally by lesbians because such displays of strength – though they still may be outside the bounds of normative femininity – are valorized and beautified by a community that is already seen as outside of normative gender to begin with. Keira Knightley’s sports bra-wearing character in Bend It Like Beckham has been similarly celebrated by sapphics because of her deviant gender presentation. Whip It, Blue Crush, A League of Their Own…I could go on.

But let’s return to the beginning of Stick It. After crashing through the window of that empty house, Haley gets arrested and sent to Vickerman Gymnastics Academy (VGA), an elite facility that is said to produce “more injuries than champions.” The reason Haley is sent here, we find out, is because she used to be an elite gymnast herself. Considered one of the best gymnasts in the country, Haley was on track for gold only to walk out in the middle of the World Championships, costing her and her whole team the medal.

Haley refuses to abandon her rebellious attitude at VGA, which causes her to clash with the other girls and with Coach Vickerman, played by Jeff Bridges. Initially, a dichotomy between Haley and the other girls is set up. They are performing gendered behavior “correctly,” and she is not, so Haley resents them for their obedience. In her voice-over descriptions of the other gymnasts, Haley describes the endlessly quotable Joanne (Glee’s Vanessa Lengies) as “zodiac sign: bitch.”

So often, tomboy characters like Haley dislike other women and are even actively misogynistic. The idea is that masculinity – or androgyny, which doesn’t really exist in mainstream films – is inherently incompatible with or hostile to femininity. Moreover, a rejection of femininity is conflated with a rejection of women. Femininity is associated with vapidity or obedience, while masculinity is associated with confidence and freedom. For the first half of the film, these are also the views Haley holds about gender, but she eventually begins to see the futility of this binary way of thinking.

Throughout the course of the film, we come to learn that Haley’s definition of rebellion and strength is not inherently better than anyone else's. When Joanne, in her miniature, feminine way, flexes and says “I have a constitutional right to bear arms,” it reminds the audience that the other girls – who Haley finds vapid and too submissive – are just as strong as she is, physically and otherwise. (It’s obvious that Haley at least respects the strength of the other gymnasts, even if she may not like them at first. Shortly thereafter Haley proudly claims: “The things gymnasts do make navy seals look like wusses.”) Later, Joanne defies her mother – who calls her a “24-hour gymnast” – and declares that she’s going to prom with one of Haley’s friends because she wants to do something for herself for once. This is Joanne’s way of rebelling, and, even though it’s very different from Haley’s, is just as significant.

Haley’s difference is visual – her style of dress indicates her gender deviance – and she exacerbates this difference in the way she acts. She wants to be different, and thinks that femininity is a trap, and masculinity is freedom. This is not to say that butches or masculine of center women are conveying this idea with their gender presentation, but it is a common perspective that is applied to tomboy characters in film and television. At first, because of her rather binary understanding of gender and identity, Haley engages with the other gymnasts in an antagonistic fashion rather than offering solidarity, but this changes when she comes to understand who the real enemy is.

The thing Haley dislikes the most about gymnastics is the rigid rules and expectations, many of which are highly gendered. She associates these rules with femininity and womanhood, two ideas she also tends to rail against. “Here we are, chasing perfection,” she says. “The problem is, perfection doesn’t exist.” At the World Championships, Haley has an epiphany that changes the course of the film. “We all wanna win, but should we be fighting each other? Or the officials?” she muses in a voice-over. Here we finally get the moment of solidarity that Haley has been refusing to participate in up until now.

When her teammate Mina (Maddy Curley) does a perfect vault routine and gets a deduction because her bra strap is showing, Haley is outraged. In response, she stands on the floor, defiantly snaps her bra strap, and then “scratches,” meaning she refuses to complete a routine. In solidarity with Mina, the other girls on Haley’s team scratch too, and soon, the movement spreads to the whole arena when the gymnasts realize they can decide who wins by scratching and declaring a default winner in each event. “I've never seen this kind of organized rebellion before,” says a commentator.

Haley’s teammate Wei Wei (Nikki SooHoo) does an unconventional hip-hop routine on the bar, and Haley does her floor routine to a Fall Out Boy song (obviously). This is a very gendered (and raced) rebellion, as the gymnasts collectively decide that the rules of gymnastics are restrictive and outdated, especially as they apply to women. Even the gymnast portrayed as the mean girl joins in the rebellion in the end, allowing Haley – considered the best in the event – to win gold for floor.

The film’s message is pretty hard to miss. It’s about breaking down rigidity and opening up space for others, something Haley succeeds in doing by the end of the film. The rules that the girls decide to ignore are very gendered and, concurrently, tied to sexuality as well. It’s no surprise that this film remains so popular and beloved, especially since the cruelty of the sport has become more well-known in recent years. Moreover, the film’s depiction of gender, and the implicit assumptions about sexuality that come with it, have clearly endeared the film to queer audiences as well, certainly engendering “gay awakenings” along the way.

Famed film critic Roger Ebert may have only given the film two stars in his initial review, but he wasn’t an 11-year-old girl in 2006, now was he? Nor did he scroll past countless gifs of Missy Peregrym’s abs on a near-constant loop. Some things are deeper and more meaningful than even the greatest thinkers of our time can comprehend.