Representation Won’t Save Us, But It Can Hurt Pretty Bad

On Netflix, Hope, and False Promises

This is the Sunday Edition of Paging Dr. Lesbian. If you like this type of thing, subscribe, and share it with your friends!

It’s been a rough month in Hollywood. Netflix has come under fire for releasing transphobic content on their platform, the IATSE (comprised of Hollywood crew members) narrowly avoided a strike after protesting working conditions, and, most horrifically, cinematographer Halyna Hutchins was killed by a prop gun on a movie set last week. At the center of these conversations is the idea that Hollywood, a business run by huge corporations, is neglecting the needs of its workers as well as – to put it in the terms of a blockbuster movie – the greater good.

When prompted for a response about the backlash against Dave Chapelle’s transphobic new comedy special, Netflix co-CEO Ted Sarandos unironically stated that “we [at Netflix] have a strong belief that content on screen doesn’t directly translate to real-world harm.” As some Twitter users quickly pointed out, this statement directly contradicts some of the content Netflix themselves hosts, as well as their actions in the past. For example, the documentary Disclosure convincingly argues that trans representation has had a huge (mostly negative) effect on the actual lives of trans people and in fact does translate to real-world harm. Moreover, Netflix actually edited the graphic suicide scene in 13 Reasons Why after concerns from mental health professionals in addition to adding a warning trailer at the beginning of each season, clearly indicating they are aware of the potential real-world implications of their content.

So, what have we learned from these controversies? First of all, if it wasn’t already clear, representation – especially representation that is produced by huge corporations like Netflix – is not going to save the world. At the same time, representation does affect the world we live in, no matter what small-minded thinkers like Ted Sarandos say.

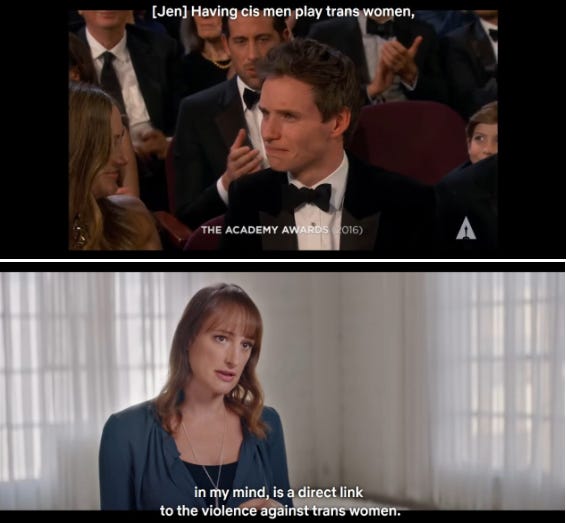

These two views are in fact compatible. Representation affects the way we understand the world– it can become a lens through which we understand difference. Obviously, this can be a positive or a negative thing, depending on the bias of each piece of media (or your own perspective). Disclosure, which is currently streaming on Netflix, argues this point quite effectively. One of the most convincing arguments in the film is put forth by trans actress Jen Richards, who suggests that cis men playing trans women in films can be directly linked to the violence against trans women in real life. As Richards argues, because this casting practice suggests to viewers that trans women are actually just men playing dress-up, when cis men find themselves attracted to trans women they panic about being gay and lash out with violence.

But, while representation can affect perception, which can, in turn, affect the real-world actions of human beings, there are some areas where representation is almost entirely divorced from material conditions. Even when purported gains occur in the area of representation – more characters of color in big franchises, for example – the outcome of such representation often negatively affects the people involved. We’ve seen a pattern of large studios “working” towards better representation by hiring and promoting actors of color, only to do absolutely nothing to stop racist attacks against them or protect these actors in any way once they are thrown into the gears of the promotional machine. Think, for example, of Kelly Marie Tran or John Boyega, whose inclusion in Star Wars was heralded as “progress,” but who were harassed relentlessly with no support from the studio that hired them. Likewise, when Ted Sarandos name-dropped Hannah Gadsby as an example of LGBTQ represention on Netflix, this only led Gadsby recieving more even homophoibc and transphobic backlash, not to mention the fact that the presence of her comedy specials don’t just “cancel out” Chapelle’s.

Moreover, the strikes happening around the country are illuminating what conditions are like within the systems that keep our world running, and indeed, within the systems that produce this very representation that we have been demanding. Last month, the IATSE (International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees) began protesting working conditions in Hollywood, agitating for safer workplaces and more reasonable workdays. An Instagram account called IATSE Stories has been posting anonymous reports from crew members sharing accounts of recurring 17-hour days and other unsafe and inhumane conditions. As of now, Hollywood has narrowly avoided what would have been a devastating strike, with the IATSE having reached a tentative agreement with the studios. (The deal still needs to be ratified by members, and not everyone is happy about the terms – see below.)

When we watch the content that platforms like Netflix host, the conditions under which this content is made are not visible. In most ways, the things we watch on TV feel divorced from the historic labor movements happening around the country right now. But the one thing these protests and strikes have brought to light is in fact the conditions under which this content is produced; the very hands that build and maintain these structures that bring these stories to life. An ideal outcome of this movement would be if it made visible the labor necessary to produce what we see on screen. In some ways, this has already happened, as the movement has gained traction and public support on social media.

However, there are many systems in Hollywood that work to conceal this labor. Indeed, the marketing strategies of companies like Netflix often work to obscure the inner workings of production, instead presenting a friendly, familiar voice as media makers. An account like @Most, which is run by queer and trans employees at Netflix, illustrates the inherent obfuscation this strategy requires. @Most – which is meant to represent the “queer voice” of Netflix – came under fire last month after simultaneously performing sincerity and sass in response to the Dave Chapelle transphobia controversy, and then the following week simply posting “brb walking out” on the day of the trans walkout at Netflix. (The black, trans employee who organized the walkout was summarily fired).

While the employees at @Most noted in their Twitter thread that they would continue to fight for better representation at Netflix (ostensibly to counteract the transphobia of Chapelle’s comedy special), this strategy doesn’t tackle the broader issues at play. As Kyle Turner writes in Mic, “there’s a frustrating disconnect between arguing for a kind of po-faced “bigger and better representation,” as opposed to recognizing the systematic and institutional issues at hand.” @Most is constrained, by the very nature of their position within Netflix, from actually interrogating the conditions under which this representation is produced, and indeed, for what purpose. Because of this, as Turner puts it, Netflix’s queer “voice” was “caught in the middle, performing disappointment without being able to sincerely convey it.”

Netflix’s strategy in regards to representation was made strikingly clear with the cancellation of their popular sitcom One Day at a Time. Season after season, the show was praised by critics and fans for its portrayal of complex topics such as immigration, depression, PTSD, gun control, and queerness, all within the confines of a typical sitcom format. So, when Netflix canceled One Day at a Time in 2019, fans were shocked. Their reasoning for canceling the show – that “not enough people watched to justify another season,” something they casually announced on Twitter – was similarly frustrating, particularly because Netflix does not release any data on viewership except for on rare occasions when the numbers look particularly impressive. The gentle tone of the tweets, the obfuscating use of “we” in the announcement, all serve to portray Netflix as a concerned friend or parent, rather than a multi-billion dollar corporation designed to bring in a profit.

The final tweet in the thread (above), illustrates how Netflix really sees representation – as something that can be quantified and easily replaced. As Kathryn VanArendonk puts it in Vulture, “The implication is that stories that carry representational heft can be swapped for one another, that this sudden gap in Netflix’s programming can be filled by something else that will simply fit into the box ODAAT leaves behind.” If representation is simply a box to check, a formula that can be endlessly repeated, then the actual content of these stories doesn’t seem to matter much at all.

Nonetheless, shows like One Day at a Time are important to people, and have undoubtedly impacted fans’ lives in significant ways. Indeed, this is where these divergent ideas about representation come together. To audiences, representation is important on a personal, emotional level, and to companies like Netflix, it’s important for the profits these connections can garner. But, this current drive for better representation is conditional, based on the perceived popularity of the idea rather than a comprehensive push for equity in all areas of production.

A push for more equitable representation on-screen must also coincide with demands for more equitable conditions behind the scenes. If we are to learn something from today’s labor movements, may it be that the content we see on screen is inextricable from the conditions in which it was produced, something that must be kept in mind if these systems are ever to change. The promise of media and of storytelling lies not in the gatekeepers of production, but in the creative and talented people who bring these stories to life with their own hands. This is where the hope resides.