Lesbian Bars and Segregation

A Brief History

This is the Sunday edition of Paging Dr. Lesbian. Plus, this week’s dispatch from the lesbian internet. If you like this type of thing, subscribe!

Last month, an initiative called The Lesbian Bar Project released a short documentary about the remaining lesbian bars in America, detailing what the owners are doing to preserve these spaces. Among other things, the documentary looked at how these bars have functioned throughout history, highlighting the delicate balance between preserving the legacy of these venues while also changing and growing with the times.

The lesbian bar is a hotly debated topic within the queer community. For older queer women, these bars are revered and their loss lamented, while for younger sapphics there is often a lack of awareness or a sense of connection to these rapidly disappearing spaces.

Lesbian bars are often discussed in conjunction with a broader conversation about safe spaces, which, though the concept has been around for decades, has been recently repurposed by a younger generation of queer people. Within the queer community, the discussion of safe spaces often revolves around one’s ability to safely express their sexuality or gender, while other equally important factors such as race, class, and ability are often considered only secondarily, if at all. This leads to the assumption that if a space, a community, or even a piece of media is welcoming to able-bodied, white, queer people, it is welcoming to all queer people.

One topic that is discussed in the film is the implicit segregation that took place at these bars. One bar, called Bonnie & Clyde’s, had what an archivist calls an "unspoken race-based quota at the door,” wherein they would only let in two or three black lesbians per night. This topic remains relevant in the queer community today. Last month, a black queer and trans event called Taking Black Pride took place in Seattle, only to be criticized by a white pride event organizer for being exclusionary. (When, indeed, the event was necessary exactly because of this history of exclusion).

In many ways, the advent of lesbian bars and their eventual rise to (relative) popularity relied on implicit self-segregation, both in terms of class and race. Though lesbian bars were, and are, considered important examples of safe spaces for queer women, they were not, in fact, safe or comfortable for everyone.

Lesbian bars have a long and storied history in the United States. Scholar Maxine Wolf “traces Lesbian use of bar environments in the U.S. to the late 1800s and the existence of bars used exclusively by Lesbians to the 1920s.” Elizabeth Lapovsky Kennedy and Madeline Davis suggest that by the 1940s, “gay and lesbian social life became firmly established in bars in most cities in the U.S.” Wolf notes that laws (including anti “cross-dressing” measures and statutes prohibiting sexual acts “against nature”) and the constant threat of violence greatly affected the experience and the physical environment of these spaces. Up until the 1970s (and even afterward) going to these bars was risky, as patrons were always under threat of violence or exposure. As Wolf puts it, “women who remained in the bar environments in the 50s and 60s had a conscious sense that they were risking a great deal to be there and decided it was worth it.”

Lesbian bars emerged in a context when it was incredibly dangerous to publicly congregate with other queer people, and this context greatly affected who felt comfortable patronizing these bars. Roey Thorpe, one of the few scholars who has done extensive research into the history of lesbian bars, notes that these spaces were often highly segregated in terms of class. While working-class lesbians would likely face violence if outed (but could potentially keep their jobs), middle-class lesbians who had jobs such as teachers would almost definitely be fired. Working-class women, accustomed to having their personal safety threatened, were more willing to fight for their space, while middle-class women, more concerned with anonymity and acceptability, were not. Thus, while working-class lesbians were willing to risk their safety to enter lesbian bars so long as they encountered a community that would protect them, middle-class women were more likely to congregate privately, creating smaller friendship groups that were less susceptible to scrutiny from straight America.

Consequently, the middle and upper-class women who hosted these private parties did not include working-class women on the guest list. While these bars being primarily working-class spaces did not preclude middle or upper-class women from entering them, working-class lesbians were informally excluded from these more upper-class parties. For one thing, some working-class lesbians worked and passed as men, and this gender deviance would have disrupted the safe “respectability” that middle-class women created at these private parties.

These issues of safety and anonymity also meant that lesbian bars were often segregated by race. Most of these working-class lesbian bars were white-owned and catered to a mostly white clientele. In their study of Buffalo in the 1930s and 40s, Kennedy & Davis note that black lesbians, greatly outnumbered by white patrons at lesbian bars, most often socialized at house parties or at straight black bars. Due to the size of the black population in Buffalo during this time, they were not able to inhabit these spaces anonymously (and thus safely), and because of this, some traveled to New York City to find a larger community. In many contexts, black lesbians were forced to choose between being singled out at (mainly white) lesbian bars or being closeted at straight black bars and parties.

Though some of these issues may seem outdated, the problem of segregation among queer women still persists today. Nikki Lane, who writes about black queer women’s spaces in Washington D.C., notes that black queer women in the city must continuously carve out their own spaces, as venues catered specifically to them do not exist (the only black lesbian bar in D.C. closed in 2013). These spaces are usually impermanent, and often take the form of monthly or one-off events and house parties. While this implicit segregation, both in terms of race and sexuality, is not literally enforced the way it once might have been, the discomfort of feeling out of place remains. As Lane notes, while black queer women “might feel ‘free’ to go anywhere in the city, they don’t always feel free to be themselves in those spaces.”

Similar sentiments have been articulated by queer black residents of Atlanta, which, though it has one of the largest LGBTQ populations in the country, is also known to be highly racially segregated. One bar (a gay bar, not a lesbian one), even put up a sign that said “No hoodies,” “No bandanas/dew rags”, “No oversized chains or medallions,” sentiments interpreted by many as meaning ‘no black or people of color allowed.’ For other QPOC, such as Asian or Latinx individuals, lesbian or queer bars catering specifically to them are virtually nonexistent.

While everyone’s relationship to the idea of physical space and community has been altered over the past year, these questions still remain. Learning about our history is one way we can better address these issues. Just because a space feels safe or welcoming to one person, does not mean it feels that way to someone else. (I encountered this dilemma frequently while working on my Master’s thesis, which focused on how queer women create safe spaces through fandom). Lesbian bars were (and are) an important part of our history and our community. It would be a shame if they disappeared entirely, but they are also not perfect, utopic spaces.

For much of their existence, the primary function of lesbian bars was safety, producing territorial practices that today might read as exclusionary. With this historical context in mind, we may begin to consider how notions of safety and inclusion/exclusion are deployed in contemporary iterations of queer spaces. Indeed, one of the issues some of the business owners in the Lesbian Bar Project documentary grappled with was the definition and usage of the term lesbian. Can it be used to define a bar that is open to people of all genders, while also centering lesbian history and experience? Is “queer” a better or more inclusive term? Personally, I’ve always felt that “lesbian” need not be – or to put it more firmly, isn’t – an inherently exclusionary or reductive term (indeed, it has been used in various ways by countless non-binary and/or trans folks over the last several decades), but I know we all have different relationships with these words.

In thinking about the importance of safe spaces for lesbians and sapphics, we need to consider who we are centering in these conversations, and who we are leaving out. Perhaps, instead of asking, is this space safe, we might instead ask, for whom is this space safe? While white queer people like myself often locate racial issues as originating outside the queer community, this is undoubtedly not the case. Communicating with and learning from one another – particularly across generations – might provide us with more clarity as the future of our community continues to take shape.

Welcome to this week’s dispatch from the lesbian internet.

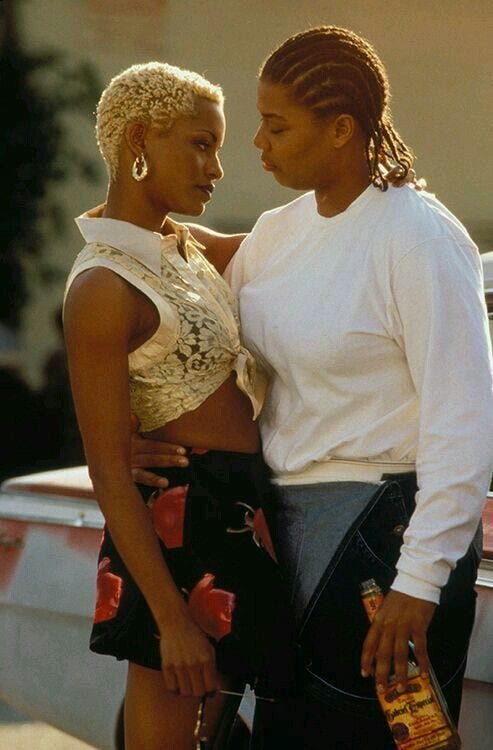

First off, some excitement was had at the BET Awards last Sunday. During the ceremony, legendary rapper, singer, and actor Queen Latifah thanked her partner and son during her acceptance speech for the lifetime achievement award. I’m not exactly sure I would call this a “coming out” because Latifah has had a whole-ass wife and child for years now, but it does mark the first time she has publicly confirmed her relationship. She is the GOAT, and should be treated as such. (Now is a good time to revisit Set It Off, if you haven’t seen it recently).

Also at the BET Awards, Lil Nas X made out with one of his male backup dancers during his performance of Montero (Call Me By Your Name). Obviously, this upset some silly little people, but it only cements his icon status in my book.

If you’re looking for something to read this week, I would recommend this retrospective on The Rosie O’Donnell Show in Vulture. I learned a lot from it, like the fact O’Donnell totally revolutionized the talk-show format, a format that would later be taken up by everyone from Ellen DeGeneres to Jimmy Fallon. Give it a read! And give Rosie some respect. I would also recommend this piece from Vox’s Emily VanDerWerff about the (in)famous short story “I Sexually Identify as an Attack Helicopter,” and how the controversy surrounding it essentially ruined the author’s life.

In other news, Niecey Nash made another horny/romantic Instagram post in which she is wearing a shirt that reads “No. Fake. Orgasms.” Niecey will never not let us know how much her wife is rocking her world, and we love her for that. In related news, JoJo Siwa celebrated Pride Month on her Instagram, noting that she’s had the best 6 months of her life since coming out. Yay!

In news that I am unfortunately excited about, a new trailer for Season 2 of The L Word: Generation Q was released this week. I think I’ve said multiple times on here that I don’t actually think the reboot is very good but they got me again with the dyke drama. Nearly 20 years later and we’re still begging Jennifer Beals to seduce us in an art gallery and then cheat on us, aren’t we? I had to pause and rewind several times to try and figure out which characters were kissing each other, which I’m sure was the point. Relatedly, check out this roundtable in Autostraddle where they break down the trailer frame-by-frame and do in fact try to decipher who’s hands are on who’s back. The women of Autostraddle also clued me in to the fact that Tina’s new wife is played by none other than ROSIE O’DONNELL??? I somehow missed this the first time around, even though I literally just read that article about Rosie’s illustrious talk show career. Gay rights!

In unexpected news, it’s been announced that Janelle Monáe will be publishing a fiction collection that expands the world of her AI, afro-futurist visual album Dirty Computer. The collection, which will be published in April of 2022, features collaborations with other storytellers that will build on the Dirty Computer universe.

In birthing (?) news, OG lesbian YouTube couple Rose and Rosie finally had their baby this week. No news on the name yet, but we did get some very intimate photos. Relatedly, Amber Heard just announced she had a baby all the way back in April (I’ve been informed that the baby was likely acquired through a surrogate), and her name is…Oonagh? More power to queer moms everywhere, I guess!

That’s all for this week, folks! Stay tuned for whatever I pull out of my brain next week. I will leave you with this photo of Ursula and Cleo from Set It Off.