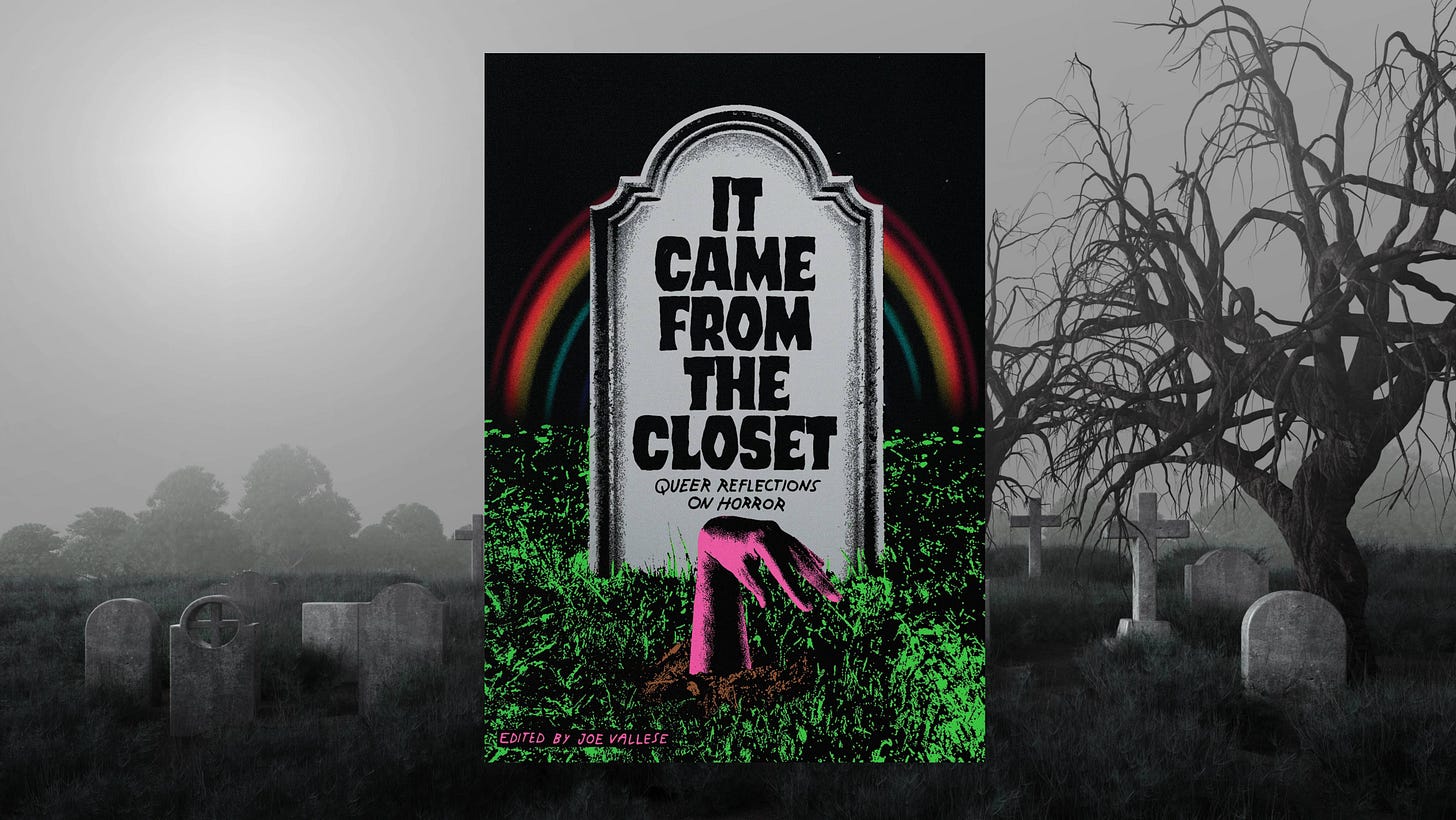

Befriend The Monsters, Find Yourself

'It Came From The Closet' Collects Queer Horror Stories

Do you like lesbians? Do you like pop culture? Then you should subscribe to this newsletter. Even better, you should sign up for a paid subscription, which will get you more sweet sapphic content and allow me to keep writing things like this.

Queer people have long had an affinity for horror, and horror has long had a fascination (or in some cases, a revulsion) with queerness. As Joe Vallese writes in the intro to a new essay collection, “It Came From The Closet: Queer Reflections On Horror,” queer people remain “titillated by the genre,” even when its depictions of queerness are less than affirming. The anthology works to excavate a variety of readings and interpretations of this sometimes fraught connection. The essays in the collection take many forms. Some look at queerness in horror, while others explore queerness outside of horror – ie. the experience of watching horror as a queer person and seeing your distorted reflection on the screen.

In recent years, discussions about queerness in horror have become more prominent, especially since it’s become more common to see actual queer characters folded into the narratives. The Fear Street trilogy, for example, was celebrated for its depiction of its queer heroines, in addition to eliding the long-standing Bury Your Gays trope. The essays in this collection take a less straightforward approach. Many of the authors take as their subject films that have been overlooked or derided in some way, either because of their lesser quality or inclusion of supposed “problematic” elements. It’s not pure commendation nor total derision, but instead somewhere in between.

Horror movies provide a symbolically rich territory for analysis, and especially for queer analysis. Unsurprisingly, several essays in the collection focus prominently on the exploration of gender within these films. S. Trimble writes that The Exorcist is “about doing gender badly,” positing that there’s something ultimately thrilling about Regan’s absolute refusal to behave as a young girl should. Horror often depicts gender transgression in some way, whether it be Norman Bates in Psycho or the virgin/whore dichotomy represented by the emergence of the Final Girl.

Gender is also tied to bodies, and bodies feature in horror movies in ways that are unique to the genre. There’s body horror of course, which is quite literally about the terrifying experience of having a corporeal form. A rigorous discussion of what it means to have a body is something that features prominently in both queer theory and contemporary debates about transness. In her essay about In My Skin, Jude Ellison S. Doyle writes that, according to the ideology of TERFs, “transmasculinity is body horror.” She goes on to argue that the real horrors are often displaced onto the body of The Other, especially when this figure looks different than the person behind the camera. The subversion of gender norms is something to be feared, such films seem to argue.

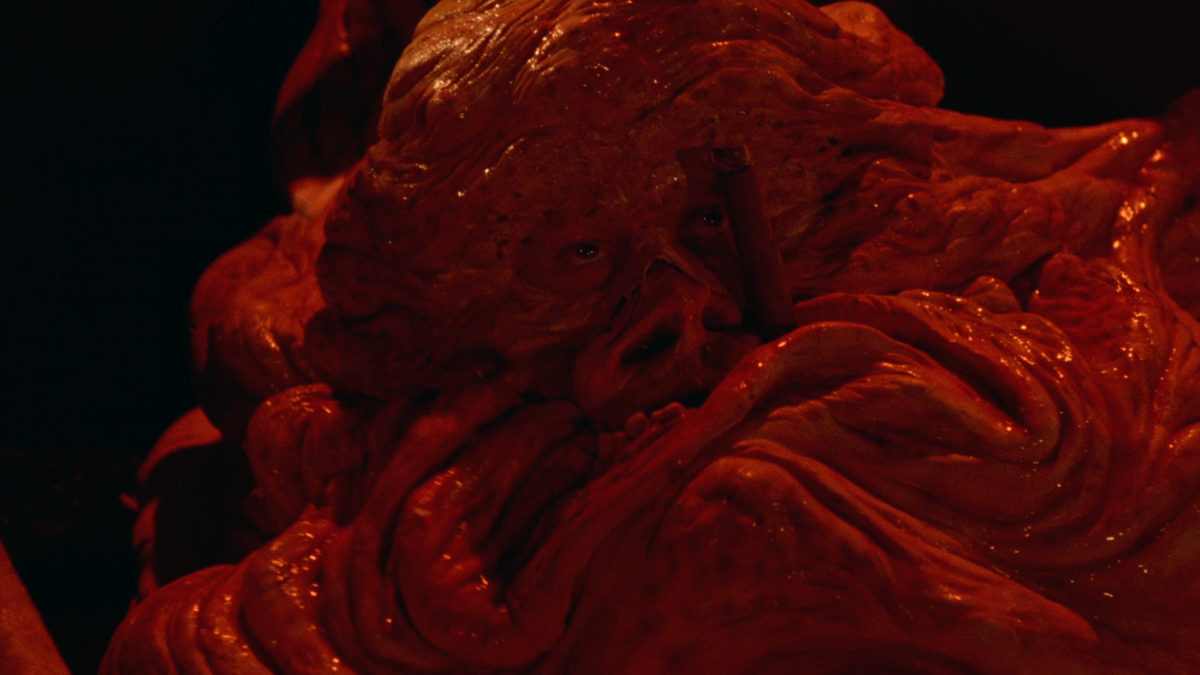

You can’t talk about bodies without talking about boundaries, as having an awareness of one’s body is tied to the realization that there is such a thing as the Self and the Other. (And indeed, that there is no such thing as a Self without an Other). The best representation of the queer possibilities of boundary-blurring in horror is the blob monster. In their essay about The Blob and Society, Carrow Narby writes that blobs “resist legibility,” which is exactly what makes them so powerful (and dangerous). “The blob’s relationship to queerness is a product of its basic symbolic function. The blob dissolves boundaries,” Narby goes on, invoking Julie Kristeva’s theory of the abject. The blob is horrifying, but also alluring. “The blob represents an absolute and unattainable intimacy,” Narby writes, as this intimacy results in the total dissolution of the Self and the Other.

In one way or another, everyone erects boundaries between themselves and others. In horror films, the most obvious symbol of this barrier is the genre’s most common disguise: the mask. The idea that masks are symbolically relevant to queer people is not new, but there is clearly more to be said on the topic. One of the most famous horror movies of all time, John Carpenter’s Halloween, is still rife for exploration. “The opening of Halloween is a coming-out story,” Richard Scott Larson writes in his essay about the film. Michael Meyers is unmasked at the start of the film as a child and at the end by Laurie Strode, who once again reveals his monstrous face.

Identifying Michael Meyers as a queer character might not seem like a revelatory act, but the notion of unmasking is a rich subject for queer analysis. In their essay about Eyes Without a Face, Sachiko Ragosta argues that “Transness is not a masking but rather an unmasking.” When the film’s protagonist, Christiane, finally rejects her father’s desire to give her a legible face, it represents her moment of freedom, despite the fact that it means she has also rejected any sense of normalcy. As human beings, we are constantly “read” by others, and must choose whether to wear a mask or unearth the truth from within. For trans and non-binary people, this is a daily dilemma. “As long as I am subjected to this unconsented reading of my body, I will desire nothing more than facelessness,” Ragosta writes, eulogizing Christiane as a figure of queer resistance.

It may already be obvious to you that the authors of these essays approach their subjects from a variety of different perspectives. Indeed, that is one of the joys of media criticism and the filmgoing experience as a whole – the ability to bring your own experiences to the table. The essayists all find themselves coming from unique vantage points, which means the collection contains several different examples of how one might “read” queerness into horror.

You might call some of these essays in the anthology queer readings, broadly speaking. Jen Corrigan argues that Jaws is a poignant representation of queer intimacy, as the three men on a boat find themselves exploring affection and closeness despite their harrowing circumstances. Laura Maw’s essay on The Birds might make you reconsider the film entirely, as her exploration of the relationship between Melanie and Annie Hayworth brings the film’s unfulfilled sapphic romance to the surface. Grant Sutton writes about Friday the Thirteenth Part III, imbuing the film with queer meaning by connecting it to his own fears about living as a gay man underneath the looming threat of HIV and AIDS.

In some cases, these queer readings double as reparative readings – a concept first proposed by queer theorist Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick – as the authors argue that their chosen films are actually affirming or subversive in some way. One of the most rousing examples of this exercise is Carmen Maria Machado’s essay about Jennifer’s Body, in which she argues that the film powerfully explores the “temporally unmoored” nature of bisexuality in a way that few other films have. Machado rejects the notion that “problematic” queerness is something we need to be on the lookout for, concluding that “the project of identifying “false” or performative” queerness is dead in the water.” Viet Dinh writes about Sleepaway Camp, a film that is often (rightfully) considered transphobic but that might offer us more than meets the eye. What is interesting about this notion of “reading” from different angles is the way it enriches our engagement with these texts. Divergent readings of a film, Sarah Fonseca writes, will “not compete with but elide my own, forming a rich tapestry of narratives.”

But not every author featured in the collection is interested in excavating the kernels of gratification hidden in these films. There are many ways in which horror films have injured queer and trans people, and holding space for those experiences is just as important as reclamation. In her essay about The Ring and Pet Semetary, Zefyr Lisowski writes about growing up trans and disabled and how this factored into her experience of watching these films. “If you first see yourself in a host of ghosts, what does it mean to live despite that?” She asks. Lisowski is not interested in flipping the script and offering up some sort of salvation but instead takes a long, hard look at what it means to come into ourselves while being surrounded by the things that hate us. “These movies hurt me and I kept on watching them. There’s nothing redemptive about that,” she writes.

There is a compelling ambivalence to many of these essays, more rigorous than it is unsure. Taking The Leech Woman as his object of study, Jonathan Robbins Leon explains how the film’s horrific nastiness is like a balm to his still-evolving sense of self. “Shame is a part of my identity. Having spent so long in its embrace, I sometimes need to feel it wash over me again to know that I am myself,” he writes. Discussing The Wolf Man, Tosha R. Taylor writes that she has always had an affection for monsters rather than heroes, an affinity that is neither bad nor good, but simply true. Horror movies can and have been many things for queer people: an escape, a harrowing confirmation, an uneasy alliance. In any case, the unearthing of the truth is the task at hand.

There is a haunting that has occurred here. These moviegoers have been haunted by these films, or in some cases, the films themselves have been haunted by the specter of queerness. Thus, these authors’ task has been to unsnarl these complicated entanglements, excavating meaning from a jumbled mess of feelings and facts. What’s most interesting about this project is that it reveals that the occurrence of watching a film is as much about the person watching as it is about the film itself. What does the body feel, and what does the mind know? The intersection of these factors is where the real delight of film criticism lies.