Basic Instinct(s)

The Enduring Appeal of Evil Sapphics

This is the Sunday Edition of Paging Dr. Lesbian. If you like this type of thing, subscribe!

In 1992, the erotic thriller Basic Instinct, starring Sharon Stone and Michael Douglas, was protested by gay rights activists outside the theater. The protesters objected to the film’s ostensibly derogatory representation of queer women, all of whom are depicted as psychotic and/or wind up dead. Despite the initial controversy surrounding its release, the film has continued to grow in popularity and has even become something of a lesbian cult classic in spite of its complicated politics. I watched the film for the first time last year and was struck by the fact that while it is certainly offensive in many ways and by no means “positive” queer representation (though perhaps this need not be the goal to begin with), it is also utterly, unavoidably, captivating.

(Spoilers ahead!) Basic Instinct follows detective Nick Curran (Michael Douglas), who is on the hunt for a killer who kills their victims with an ice pick. His prime suspect is crime novelist Catherine Tramell (Sharon Stone), with whom he immediately (and predictably) falls passionately in-lust. (Spoiler alert – she did it!) During all of this, Catherine also strings along her “girlfriend” Roxy, who winds up dead, and we later find out that Catherine also had an affair with Nick’s psychologist Beth (Jeanne Tripplehorn), who dies as well. The most famous moment of the film is certainly the opening-of-the-legs interrogation room scene (the explicitness of which Stone did not consent to), but the film is chock-full of off the rails, sex-crazed, moments like these that director Paul Verhoeven (who also directed Showgirls) is known for.

If I were to argue that the basis for Basic Instinct's appeal lies in the fact that Sharon Stone is very very attractive in this movie, I think most readers would agree. Her slinky movements, her seductive eyes, and the sheer force of her magnetic allure make it difficult to deny the film’s charm, regardless of any reservations one might have about the plot. As someone who has spent years studying queer representation in the media and the effects it has on audiences, I was completely enraptured by Stone’s performance, despite simultaneously feeling kind of like the film itself was committing a hate crime against me. To put it simply, Sharon Stone is incredibly talented (just watch her magnificently unhinged turn as an alcoholic mob wife in Martin Scorcese’s Casino), and incredibly, undeniably, well, hot.

But perhaps there is something else that as lesbians or queer women we find alluring about characters like Stone’s Catherine Tramell. It may be that the enduring appeal of the film can tell us something about our own relationship to fantasy and the thrill of recognition, however distorted or perverted. Indeed, I wonder if the reason these types of characters remain so appealing is that there is a long history of this type of ambiguous representation of and for sapphics.

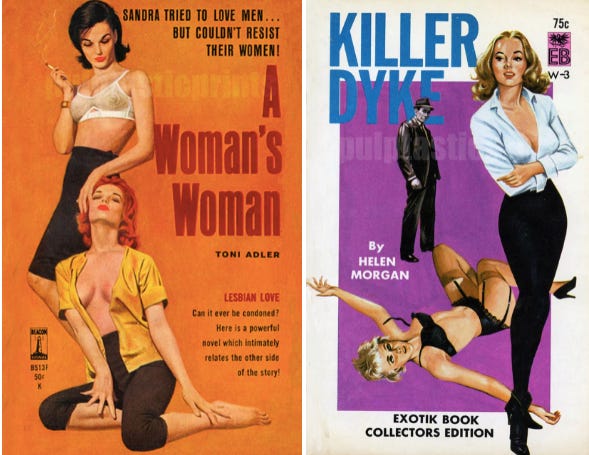

Travel back several decades into lesbian history and you will find one of the most influential types of lesbian media – the lesbian pulp novel. These novels had their heyday in the 1950s and early 1960s, and one need only look at their covers to see the connection between these books and more modern depictions of “deviant” sexuality as portrayed in films like Basic Instinct. Nearly every lesbian pulp cover depicts two women positioned in a particular way – one sitting or positioned lower in the frame, and the other standing domineeringly above her. While some of these novels were actually written by queer women using pseudonyms and therefore contained less derogatory messaging, the general perception of the genre, and of lesbians themselves, was that they were deviant and predatory in nature. Unsurprisingly, this type of parasitic power imbalance is at the center of Basic Instinct as well. While Catherine’s “girlfriend” Roxy (pictured above) seems to be there of her own volition, it is very clear that she is entirely at Catherine’s mercy and is frequently forced to put up with Catherine’s male lovers.

Despite their often pejorative messaging, these novels were consumed in vast numbers by queer women themselves. Lesbian archivist Joan Nestle has called these novels “survival literature,” and scholar Yvonne Keller notes that they were “coveted and treasured for their sometimes positive and sometimes awful but decidedly lesbian and decidedly available representation.” Indeed, lesbian pulp novels were significant in lesbian history because they both inspired lesbian self-identification and encouraged lesbians to envision their own cultural spaces. What stemmed from this market for tantalizing sexual perversity was not only an unexpected lesbian readership, but also a new generation of lesbian authors who interpreted the genre in ways that were more amenable to their own self-perception.

Deviance was portrayed similarly in films of the time, though perhaps in a less provocative manner owing to the censorship of the Hollywood production code. The Children’s Hour (1961), starring Audrey Hepburn and Shirley MacLaine, was one of the only films of the period that openly depicted lesbianism, and it ends (spoiler alert) with MacLaine’s lesbian character hanging herself out of shame for what she feels. Similarly, scholar Ann Ciasullo has written of the “Women-In-Prison-Narrative” (which she dates from the 1920s to the 1960s) and the ways in which it provided space for an exciting and titillating exploration of female homosexuality while at the same time re-inscribing heterosexuality as the norm – quite literally containing queer desire.

Fundamental to all of these examples is the notion of deviance – that lesbianism is a type of monstrosity that must be contained at all costs, but that also may be intrinsic and unavoidable. Most lesbian pulp novels (particularly what Keller calls “virile pulps,” which, as opposed to “pro-lesbian pulps,” were written by men for a male audience) ended in such containment, often concluding in death, institutionalization, or a “return” to heterosexuality. Similarly, while Catherine Tramell’s moral depravity is the driving force of the film, Basic Instinct also ends with a similar type of containment, as Catherine decides at the last minute not to kill Michael Douglas’s character with an ice pick, instead choosing to (at least temporarily) live a nice domestic life with him.

What is interesting about lesbian pulp novels – as well as other ostensibly homophobic or biphobic films like Basic Instinct – is not simply that they existed, but that they were consumed, and consumed at times with great pleasure, by lesbians and bisexuals themselves. Despite the ways in which these novels often condemned the women whose stories they told, the pulps had an undeniable effect on the generation of lesbians that read them. They helped women to see themselves for the first time, and to realize they weren’t alone. They even inspired some women to move to places like Greenwich Village – described in the novels as lesbian meccas – to find others like them.

It seems though, looking at the current state of media, that we have surpassed the need for such examples of queer deviance. A film like Basic Instinct, which came out nearly 30 years ago, doesn’t seem like it would fit in the current media landscape anymore. Indeed, Stone herself has suggested that the film probably wouldn’t get made today. Nonetheless, it appears that there continues to be something captivating about lesbian or bisexual monstrosity that as viewers we can’t quite deny.

Though the trope of the psychotic lesbian has been increasingly derided over the past several decades, it continues to haunt (or perhaps possess) popular media today. We might think here of the psychopathic queer killer Villanelle in Killing Eve, or Blake Lively’s turn as an evil, vaguely sapphic suburban mom in the Gone Girl-esque A Simple Favor (2018). Both of these examples are enjoyed – or at the very least not openly condemned – by sapphics themselves. In Killing Eve this enjoyment primarily comes from the deliciously erotic relationship between Eve and Villanelle, as well as the genuine nuance with which Villanelle’s character is written and performed. On the other hand, the charm of a film like A Simple Favor lies not so much in its nuance (there isn’t much to speak of), but rather in the fact that Blake Lively is costumed almost exclusively in perfectly tailored suits. More recently, Rosamund Pike’s evil capitalist lesbian in the Netflix original I Care A Lot has captured the hearts of sapphics who are willing to overlook her dastardly deeds.

Perhaps the reason we continue to enjoy, or at least are fascinated by evil or violent queer women is not only that they are now more thoughtfully produced, but also that we now have more language with which to speak about them. As a lesbian, I am able to enjoy Basic Instinct despite its sexist and homophobic/biphobic overtones because I am familiar enough with the trope of the evil lesbian or bisexual and comfortable enough with my own sexuality that I can appreciate the delicious fun of it all. (And it is fun). We have, as queer people, all confronted this idea of predatory queerness, and in many cases have internalized this notion within us. It may be that these ideas remain popular because there is something liberating in directly confronting and reveling in the stereotypes that have long been used as a weapon against us.

Though the idea of “surviving” off of whatever queer media you can get your hands on still feels in some ways relatable today – the mantra “I’ll watch anything if it’s gay” continues to reign supreme within many fan communities – we are not quite in the same position as sapphics of the 1950s or the 1990s. But regardless of the differences between then and now, sapphics continue to discover new ways to find reflections of themselves – whether distorted or realistic – in the media that populates our lives. Perhaps we are no longer surviving off the consumption of these monstrous versions of ourselves, but instead reinventing and regurgitating the concept of monstrosity itself. Three cheers for evil queers.